-

“The lights are going out”: Serkin, Busch Quartet, Brahms

It must have been a Thursday in 1977 or 78. After school, my father drove me to my clarinet lesson with my new teacher – John Melvin, who was Head of Music at Oxford High School. He was a warm and encouraging mentor and taught music as an expressive language, not overly concerned with the finer points of clarinet technique. (He was also the inspirational conductor of the local youth orchestra – which I joined soon after: coaxing, rather than commanding, the best from his young players.)

His teaching room was a mess, the grand piano hardly visible under piles of scores, books, and records. He hardly ever demonstrated on the clarinet (he didn’t play much in those days), but he passed on lots of knowledge and insights from his teacher, Frederick Thurston (1901-1953, founding principal clarinettist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra), and other musicians of an earlier generation.

At this particular lesson, I think we must have been working on one of the Brahms sonatas, and he started enthusing about the legendary English clarinettist, Reginald Kell – still then regarded as something of an eccentric for his use of continuous vibrato. As I left the lesson, in one hand I held my clarinet case and music, and under the other arm I held a brown square box, carefully trying not to drop it before I reached the car. The box contained four original shellac 78rpm discs of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet, performed by Kell and the Busch Quartet.

Remarkably, our stereo gramophone could still play 78s (in fact, I’m pretty sure that, as well as 78, 45, and 33 & 1/3 speeds, there was even a 16 rpm setting!).

At home we had an LP of the Kell recording with the Fine Arts Quartet, recorded in the US in 1951. But this 1937 London recording with the Busch quartet was something else: sinewy, expressively free, but also rhythmically taut, and imbued with a sort of sweet pain – almost unbearably heart-wrenching, yet ultimately consoling.

This was my first exposure to the sound world of the Busch Quartet. Beyond the scratches and fizz of the old recording, I marvelled at this tradition of mittel-European music-making, seemingly still rooted in the rich soil of nineteenth-century chamber music performance practice, but with a steely, modern fidelity to the score – the perfect combination of heart and intellect.

Later on, I discovered more Busch Quartet recordings, reissued on LP and then CD: the Beethoven late quartets, of course; Schubert chamber music, and duo recordings of Adolf Busch – the first violinist – with the pianist Rudolf Serkin. And it’s to one of the great collaborations of Serkin with the full quartet that I want to turn now: the EMI recording of Brahms’s Piano Quintet in F minor, op.34, made at Abbey Road Studios, London on 13 October 1938.

Five years before this recording was made it was the centenary of Brahms’s birth. The year 1933 was significant for more sinister reasons, of course, as this brief news report in Time magazine from 1 May 1933 makes clear:

In Manhattan last week arrived bristly haired, professional Violinist Adolf Busch bringing to the U. S. for the first time his famed Busch Quartet and his young protege Pianist Rudolf Serkin. Day before they landed came news that Busch, like many another German musician, had found Adolf Hitler’s government more than he could stomach. Busch had been engaged for Brahms centennial concerts in Hamburg this month, but Pianist Serkin, a Jew, was not to be allowed to play. Violinist Busch withdrew.

Adolf Busch never played in his homeland again. He was already living in Switzerland and attempts to lure him back to Germany were answered with somewhat stringent conditions: “If you hang Hitler in the middle, with Goering on the left and Goebbels on the right, I’ll return to Germany.” He wasn’t one for sitting on the fence!

By 1938, the only two European countries where Busch and Serkin would play were Switzerland and Britain.

The Busch-Serkin relationship was one of the great musical partnerships, and their chamber music groupings were literally family affairs: Adolf Busch became Serkin’s father-in-law when Rudolf married Adolf’s daughter Irene in 1935, and Adolf’s brother Hermann played cello in the quartet. And they worked so intensely together that they often performed concerts from memory (including complete cycles of the Beethoven violin sonatas).

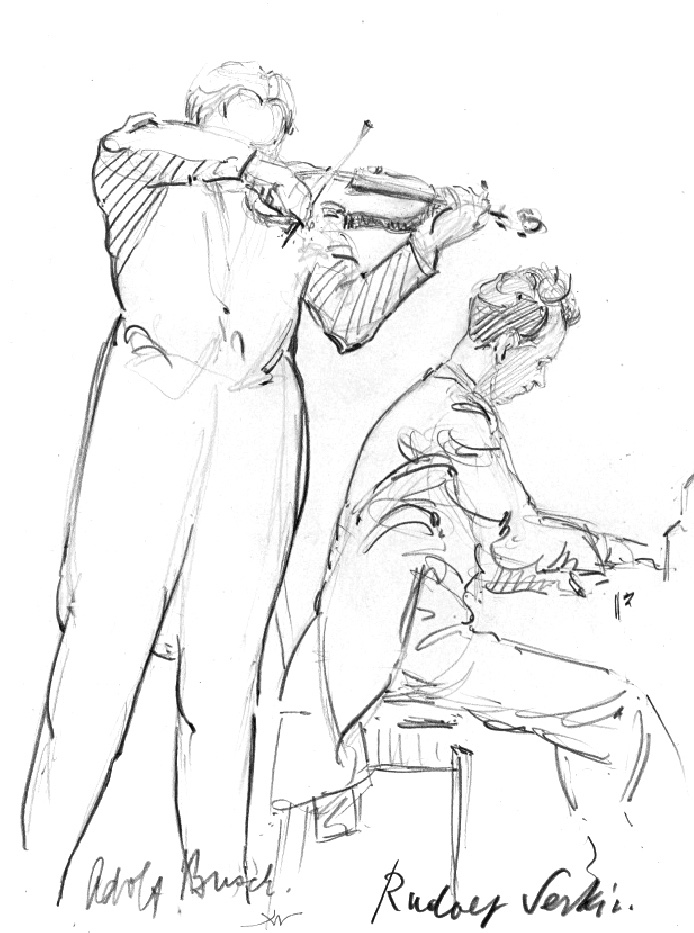

Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin at the Brussels Conservatory in 1935, by Hilda Wiener (1877-1940) Let’s now consider the date of this Brahms recording: 13 October 1938: less than a month before Kristallnacht (9-10 November), and just a few days after German forces started to occupy the Sudetenland, including the town of Eger (Cheb in Czech) – Rudolf Serkin’s birthplace. And seven months earlier (12 March) German troops had entered Austria, trapping Serkin’s mother and his siblings in Vienna.

Adolf Hitler driving through the crowd in Cheb (Serkin’s birthplace) on 3 October 1938 In London on 30 September, Neville Chamberlain stood outside 10 Downing Street, having returned from Munich, believing he had given Hitler everything he wanted, to prevent war: “My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time. We thank you from the bottom of our hearts. Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.”

Winston Churchill thought otherwise, of course, and on 16 October he gave a radio broadcast to the United States from London, in which he said:

The stations of uncensored expression are closing down; the lights are going out; … The light of civilised progress with its tolerances and co-operation, with its dignities and joys, has often in the past been blotted out. But I hold the belief that we have now at last got far enough ahead of barbarism to control it, and to avert it, if only we realise what is afoot and make up our minds in time.

What has all this got to do with a piece of chamber music by Brahms, written 70 years earlier, and recorded on an autumn day in a studio in St. John’s Wood, north London? My answer is: nothing and everything.

-

Light refreshment: the piano singles (ISCM 1922/23)

As an antidote to my previous two posts, and to show that modern music wasn’t all about serious soul-searching, here is a playlist of 14 minutes of pure delight: five short piano pieces, chosen for performance at the first festivals of the International Society of Contemporary Music in 1922 and 1923.

- Francis Poulenc: A Bicyclette, No.9 from Promenades (1921)

- Egon Kornauth: Walzer, from 3 Klavierstücke, op. 23 (1920)

- Lord Berners: Strauss, Strauss, et Strauss, No. 3 from Valses Bourgeoises for piano four-hands (1917)

- Manuel de Falla: Cubana, No. 2 from 4 Piezes Españolas, played on a Duo-Art piano roll (1906-09)

- Igor Stravinsky: Piano-Rag-Music (1919)

Lord Berners in his mini Rolls Royce -

Air from another planet: seriously modern string quartets (ISCM 1922/23)

Unless you have three and a half hours to spare and a particularly robust constitution, I would not recommend listening to this playlist in one go. A dozen pieces for string quartet performed at the two earliest festivals of the International Society of Contemporary Music in Salzburg (year 0 in 1922, year 1 in 1923) – mostly serious, mostly written in an extended tonal language, if not actually atonal, can be hard going. But when heard in the order that they were written they provide a fascinating aural timeline of early musical modernism. (I’ve added Percy Grainger’s Molly on the Shore at the end as a bit of light relief.) Here is the complete list.

- Schönberg: String Quartet No 2, op. 5 (1907-8)

- Webern: 5 Movements, op. 5 (1909)

- Berg: String Quartet, op. 3 (1910, rev. 1920)

- Stravinsky: 3 Pieces (1914)

- Milhaud: String Quartet No. 4, op.46 (1918)

- Stravinsky: Concertino (1920)

- Hába: String Quartet No. 2 (1920)

- Wellesz: String Quartet No. 4 (1920)

- Hindemith: String Quartet No.3, op.22 (1921)

- Walton: String Quartet No. 1 (1919-22)

- Krenek: String Quartet No. 3, op. 20 (1923)

- Grainger: Molly on the Shore (1907)

Artistic circles: Arnold Schönberg by Richard Gerstl (1906), Anton Webern by Egon Schiele (1917), Alban Berg by Arnold Schönberg (1910) The quartets by the three A’s of the Viennese avant-garde – Arnold, Anton, and Alban – are febrile, inward-looking and intense. And this trio of works is a superb way of entering the minds of composers who wanted to get into the minds of attentive listeners in a direct and unfiltered way, without being bound by the rules of traditional musical logic.

In a revealing letter to his fellow composer Busoni, dated 13 August 1909, Schönberg presents a mini-manifesto of his compositional aims at this time. It’s worth quoting at length as it gives a vivid insight into why the music of these three composers can be difficult to grasp, but also more deeply appreciated if listened to in a certain way.

I am striving for: complete liberation from all forms. Of all the symbols of connection and logic. So: away from “motive work”.

Away from harmony as cement or building block of architecture. Harmony is expression and nothing other than that.

Then:

Away from pathos!

Away from 24-hour continuous music; from built and constructed towers, rocks and other gigantic stuff.

My music must be short. Concise! In two notes: not building, but “expressing“!!

And the result I hope for:

No stylised and sterilised permanent feelings.

These don’t exist in humans:

It is impossible for humans to have only one feeling at a time.

We have thousands at once. And these thousand add up as little as apples and pears add up. They go in different directions.

And this colourfulness, this diversity, this unlogicality [Unlogik] that our sensations [Empfindungen] show, this unlogicality that has the associations that manifest in the circulation of the blood, in some sensory or nerve reaction, I would like to have in my music.

It should be an expression of sensation, just as the sensation really is that which connects us to our unconscious, and not a conflation of sensation and “conscious logic”.

The letter in its original German can be found here.Much has been written about these three quartets and what was new in the music – the addition of a soprano voice to the last two movements of the Schönberg quartet, for example, and the extent to which each of the composers was moving towards atonality. And the three composers have their distinct differences, of course. But I want to draw attention to what they have in common, not from a musical-technical angle, but from a musical-psychological aspect: the listener’s point of view (or the aural equivalent of that visual phrase), using Schönberg’s words as a guide.

Although it is perhaps the Webern Movements that align most closely with Schönberg’s “manifesto”, all three works can be heard through the prism of non-logical freedom from conventional form. We don’t have to try to follow a harmonic narrative or architecture. We can hear the music mirroring or echoing our multi-layered thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations. In fact we can allow the music to make the case for the indivisibility of mind and body.

I do not feel qualified to write about the clear parallels with Freud’s researches taking place in contemporary Vienna, but Schönberg’s mention of the word “unconscious” can not go unnoticed. On the Freud Museum, London’s website we can read the three particular characteristics of the unconscious that Freud identified :

- It allows contradictory ideas to coexist side by side

- Its contents do not have degrees of ‘certainty’ in the way that conscious ideas do

- Unconscious ideas are not arranged in any chronological order.

These characteristics can also apply to the music from this period of the Second Viennese School composers. And – like the unconscious – this music is not randomly irrational: it follows its own patterns, seemingly spontaneously, separately from “conscious logic”.

Stravinsky by Picasso (1920) If the Viennese modernists look inwards, Stravinsky and his followers look outwards, celebrating movement and the physical world: more objective, less subjective.

But an interesting listening experiment (easier to accomplish than ever before) of interspersing Webern’s Five Pieces with Stravinsky‘s Three Pieces reveals more similarities than one might expect. Both composers use the string quartet like a painter’s palette and mix new colours and timbres. Their music is aphoristic, fragmentary. Brief flashes of polytonal harmony in both works stimulate the ears in the same way that oblique rays of sunlight can momentarily highlight previously unseen aspects of the physical world.

We can hear more sustained use of polytonality in the delightful pithy 4th String Quartet by Darius Milhaud: two very short outer movements encasing a sombre slow movement. The first movement’s main theme consists of two instruments playing in F major, while the other two are in A major.

Of the remaining works on the playlist, there is one oddity: Alois Hába’s String Quartet in the Quarter-Tone System – a brave experimental system that didn’t catch on, and makes me feel slightly nauseous, I must admit.

The other quartets are all examples of the trend in the early 1920s to move away from what some saw as the excesses of Expressionism, which had itself grown out of late Romanticism. It was a conscious attempt to write music in a more objective, sometimes neo-classical, style.

When in the hands of a master – like Stravinsky in his Concertino – the results can be invigorating and innovative, especially in the deployment of sparkling asymmetrical meters and rhythms. But when less-imaginative composers write in this style, the effects can be underwhelming.

I have given the quartets by Wellesz, Hindemith, Walton (an amazing technical achievement for the still teenage composer), and Krenek a fair hearing with repeated listening, but I have to confess that I am reminded of the opening lines of T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men (1925):

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw, Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;A generous interpretation of these works is that they – like Eliot’s poetry of the time – are a reflection of the aftershock of the First World War, which must have left many Europeans emotionally drained and numb.

Amar Quartet (1925), from left to right: Licco Amar, Rudolf Hindemith, Paul Hindemith, Walter Caspar I’m afraid I’ve always had a blind spot when it comes to the music of Paul Hindemith, and I find it difficult to understand the status he achieved in twentieth-century music. He certainly had a gift for writing melodies that go nowhere in particular and maybe the grey blandness of his harmonic palette was inoffensive enough for him not to fall out of favour with the musical establishment in Europe and America (where he settled in 1940). But as a performer – especially as the viola player in the Amar-Hindemith Quartet – his influence was well-deserved. This quartet gave the first performances of several of these pieces, and remarkably there are recordings of three of them, made not long after their premieres.

These 78s must be some of the earliest recordings of what we now think of as contemporary music. They are high quality performances with a great deal of technical skill and virtuosity (their interpretation of the very challenging Stravinsky Concertino knocks a minute off present-day recordings), even though it is difficult to hear some of the detail in these pre-electric sides. Here are the three recordings:

Stravinsky: Concertino for String Quartet, recorded 1925 Hindemith: String Quartet No.4, Op.22, recorded 1925 Krenek: Waltz from String Quartet No. 3, Op. 20, recorded 1925 Even more remarkably, Hindemith must have had such sway with the record companies, that just a year later his ensemble re-recorded the same complete quartet to take advantage of the new electric recording technology:

Hindemith: String Quartet No.4, Op.22, recorded 1926 The string quartets performed at the first ISCM festivals span the pre- and post-war period, and serious times demand serious music. The twenties weren’t roaring all the time. The selection committee seemed to have their collective finger on the pulse of what was new and worthy of attention. I hope – in future articles – to follow this trail to discover how the musical trends revealed here developed in subsequent festivals.

-

Six of the best: violin sonatas for a new age (ISCM 1922/23)

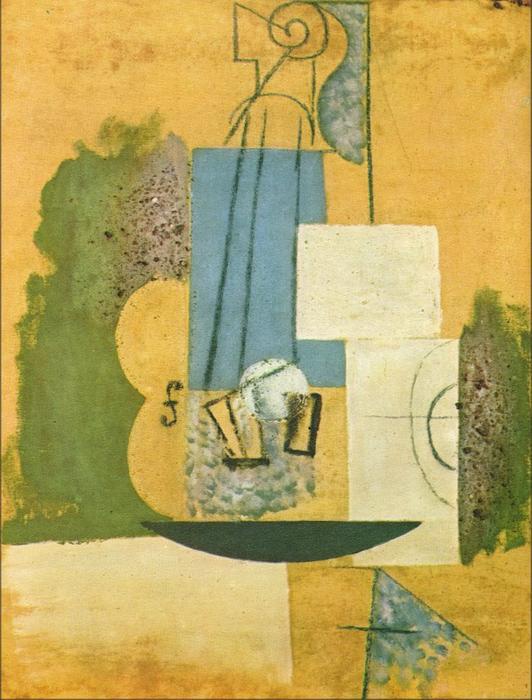

In the early years of the twentieth century, the violin achieved iconic status in European culture in an almost literal sense. Whereas Renaissance painters looked to the Madonna and Child as worthy subjects for art, modernist artists – putting their faith in more secular imagery – often turned to the violin to represent one of the peaks of human achievement for a new post-religious age.

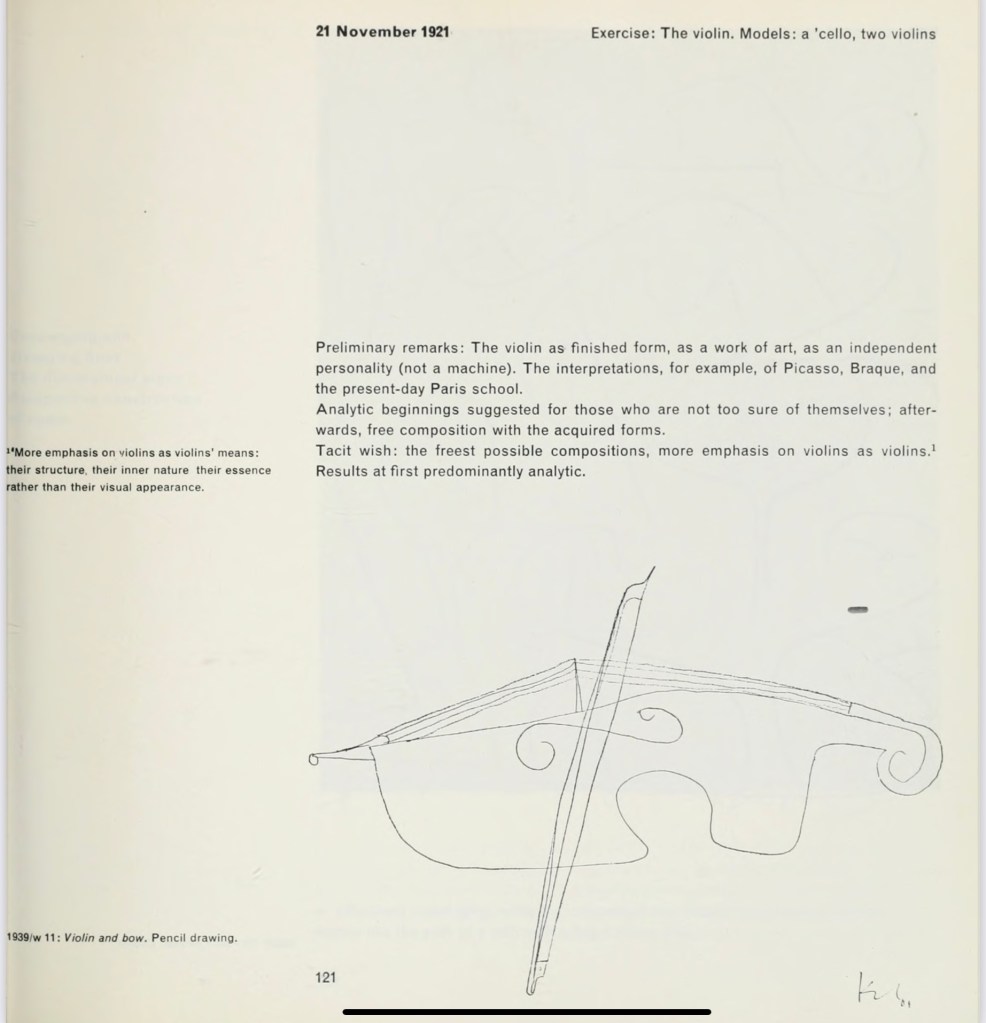

Violin (c.1912) by Pablo Picasso In his notes for a lecture at the Bauhaus, Weimar in November 1921, the Swiss artist Paul Klee asks his students to treat the violin “as an independent personality (not a machine)”. This is the violin representing human individuality in opposition to the anonymity of the machine age.

The violin – both as a perfectly crafted musical instrument and as a vehicle for supreme human artistry – combined urban high art and rural folk culture: the salon as well as the tavern. It is no accident that the violin plays a key rôle in Stravinsky’s tale of the everyman-soldier, L’Histoire du Soldat (1918).

It also took centre stage in the early days of the International Society for Contemporary Music. At the first unofficial festival in 1922 preceding the ISCM’s formal founding, and the first official festival in 1923 (both in Salzburg), several recent works for violin were chosen for performance, including no fewer than six masterly violin sonatas: by Carl Nielsen (written in 1912), Leoš Janáček (1914-15, revised 1916-22), Florent Schmitt (1919), Ernest Bloch (1920), and two by Béla Bartók (1921 & 1922).

These six violin sonatas are all substantial works and, together, they illustrate the wide variety of contemporary music on offer at these early ISCM festivals, from composers outside the dominant Austro-German mainstream (from Denmark, Czechoslovakia, France, Switzerland/USA, and Hungary). Yet, despite the diversity of styles and compositional approaches, the six works have much in common. They are all serious attempts to take a traditional form in new directions and to challenge the virtuosity of performers on both violin and piano. And each sonata is drenched in human passion and intellectual inquiry, together forming a boxed set of exploratory musical narratives for a new age.

I have made a Spotify playlist of the six sonatas. I recommend listening attentively to this music. This is not music for the car stereo or for accompanying social media scrolling! What follows are “listening notes” in the sense of “tasting notes” in descriptions of fine wines, based on close listening, so don’t expect detailed analysis of the music or extensive biographical information.

The Violin Concert (1903) by Edvard Munch Composed between his third and fourth symphonies, Carl Nielsen’s Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 35 is neither expansive nor inextinguishable, with its compact and concise opening movement and a short finale that peters out like a fluttering match. The weight of the central Molto adagio, however, anchors these two flighty outer movements to solid ground.

The wandering violin theme that opens the sonata has a pre-echo of Shostakovich about it in its reticent searching. Nielsen has a liking for unusual tempo qualifiers, and this one – Allegro tiepidézzo (tepid or lukewarm) is particularly intriguing. Is it a reluctance to get involved? (The beginning is also marked senza espressione.) The rapid shifts of tonality certainly suggest a reluctance to settle down.

The stabs of pain at the start of the Molto adagio ripple throughout the rest of the movement. But this is an adagio that also contains the comfort to salve these wounds.

The finale has the spirit of a gentle scherzo, making its abrupt quiet ending seem even more premature: are we not expecting another movement to follow? The marking Allegro Piacevole (agreeable, pleasant) is also used by Beethoven as the triple-time finale to his 2nd Violin Sonata, a work that Nielsen the professional violinist was surely acquainted with. Nielsen’s Allegro – although benignly agreeable – has a slight feeling of discomfort due to the fact the the stress is mostly on the “wrong beat”: the upbeat that it starts with is felt as a downbeat, and this rather cheeky deception continues for much of the movement.

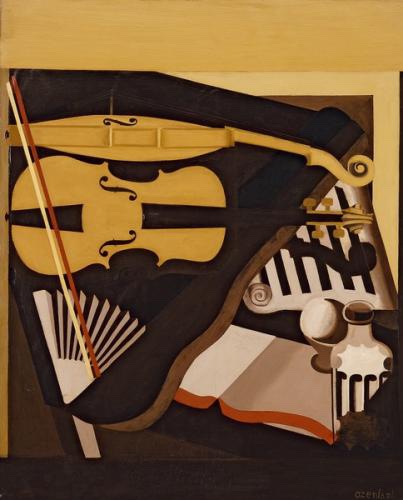

Nature Morte au Violon (c.1919) by Amédée Ozenfant All the composers featured here were in their 40s when they wrote their sonatas, except Leoš Janáček, who was 60 years young when he started his Violin Sonata, with most of his mature operas still ahead of him. This sonata is like a micro-opera in 4 acts, lasting a total of 17 minutes – a psychological drama, compelling in its compressed intensity: listening on headphones is an almost claustrophobic experience. Janáček achieves this with his technique of repeating short obsessive motifs: crystallising in three or four notes, what might take other composers a whole melodic paragraph or harmonic progression to express. And by doing this he captures states of mind and fleeting nervous emotions that more long-winded composers often miss. Whether or not this sonata was written in response to events of the First World War as some sources suggest, this music is raw, and contemporary in a genuine sense: emotions experienced in real time, not remembered with nostalgia.

Violin (1923) by Henri Mattise. “A wave swelled toward you

out of the past, or as you walked by the open window

a violin inside surrendered itself

to pure passion.” (from the First Duino Elegy by R.M. Rilke, published 1922, trans. Mark Wunderlich)While some composers scaled back their musical style in response to the straitened times immediately following the First World War when large orchestral commissions were harder to come by, others turned their chamber compositions into quasi-orchestral works instead. In Florent Schmitt’s Sonate Libre the phenomenally difficult piano part – often written across three staves – provides a pretty convincing substitute for a full symphony orchestra, with a kaleidoscopic pallete of tone colour.

Page from the score of Schmitt’s sonata: a work of art in itself. The full title of this startlingly seductive work is Sonate libre en deux parties enchaïnées (ad modum clementis aquæ), or “Free sonata in two linked parts (in the manner of gentle water)”. This subtitle invites associations of water-related adjectives to describe this music: fluid, liquid, meandering, flowing. And this is key to understanding and following what otherwise might seem a superficially amorphous piece. As Heraclitus famously wrote of not being able to step into the same river twice, this music is constantly changing – even when a phrase recurs it is never heard in exactly the same way. Schmitt clearly learnt this technique of perpetual variation (as much else of his musical language) from Debussy, whose late orchestral work Jeux (1912) exemplifies this approach.

And some of the ravishing additive harmony is aurally dazzling: listen to the chord that ends the first movement, which contains no fewer than nine different notes; or the effervescent Messiaen-like fizz of the sonata’s sparkling coda.

Green Violinist (1923-24) by Marc Chagall The Violin Sonata No. 1 by Ernest Bloch is the big discovery for me. From the very start this music grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go. It’s earthy and rough, but also passionate and sensual. The first movement kidnaps the listener and you have no choice but to be taken along for the ride. It also has a freshness of utterance with its use of distinctive modal scales, that persuade and cajole with insistent repeated motifs and hurtling rhythms.

The slow middle movement is a ghostly shadow of the first movement, as though the obsessions of the first movement continue to disturb, even when the mind and body are trying to rest.

In the finale, daylight starts to shine on the recurrent motifs and harmonies, and the final resolution on an E major chord is like weak sunshine finally appearing through the mist.

What’s remarkable about this music is how unified it is in style, with a harmonic language quite distinct from other contemporary tonal languages. There are echoes of Stravinsky, Debussy and others, but Bloch’s voice is unique and revelatory.

Violin and Guitar (1913) by Juan Gris We have a huge advantage over the original audiences at the early ISCM festivals: we can listen to these pieces again and again. This is particularly pertinent to the two violin sonatas by Béla Bartók – complex pieces that reveal more of themselves on each hearing. Hungarian as a language is famous for being unlike most other European languages, and Bartok’s music is likewise one of a kind, revealing complex aspects of thought and emotion that elude more mainstream composers.

Bartók’s Violin Sonata No. 1 bears the imprint of the soundworld of the big radical stage works of the composer’s early maturity: the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, and the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin. But as with the Janáček sonata discussed earlier, the drama is distilled down into chamber music size that, nevertheless, goes far beyond the domestic boundaries of traditional chamber music. And the first movement, in particular, stretches the bounds of tonality too, with its ever-widening intervals in the violin line and dense chords, whether arpeggiated or not, in the piano part.

The unaccompanied violin melody that opens the Adagio second movement is almost 12-tone-row-like in its avoidance of a tonic root. When the piano enters with the first pure triadic chords of the whole sonata, it is like balm for the soul, and here we enter the dreamworld of Bluebeard’s castle grounds.

For the finale, we are hurled into a manic folk dance, occasionally stopping for breath, before launching into ever wilder dashes for the finish.

Violin and Glass (1914) by Georges Braque Bartók’s Violin Sonata No. 2 can be heard almost as a continuation of the first sonata (the two works follow each other in the composer’s catalogue of works), but there is an inward turn in the atmosphere of the first movement. The ideas are fragmentary, exploratory (a musical equivalent of the cubist paintings shown here), and even perhaps a bit hallucinatory – like thoughts one might have when unable to get to sleep. Only the recurring tender brief melody, first heard in the opening bars, gives some solace: the gentle rocking of a line from a lullaby.

The second movement – which follows without a break – makes sense to me if I hear it as a response to the age of machines and production lines. Yes, it stems from folk dance again, but this time there is something almost non-human about it. The Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R., which introduced the word robot to the world was premiered in 1921 (and already translated into 30 languages by 1923), and Bartók was not immune from being affected by the zeitgeist. Only at the very end is the lullaby phrase alluded to, and the piece ends – astonishingly – on a quiet, simple C major triad, the three notes spread over a range of five octaves.

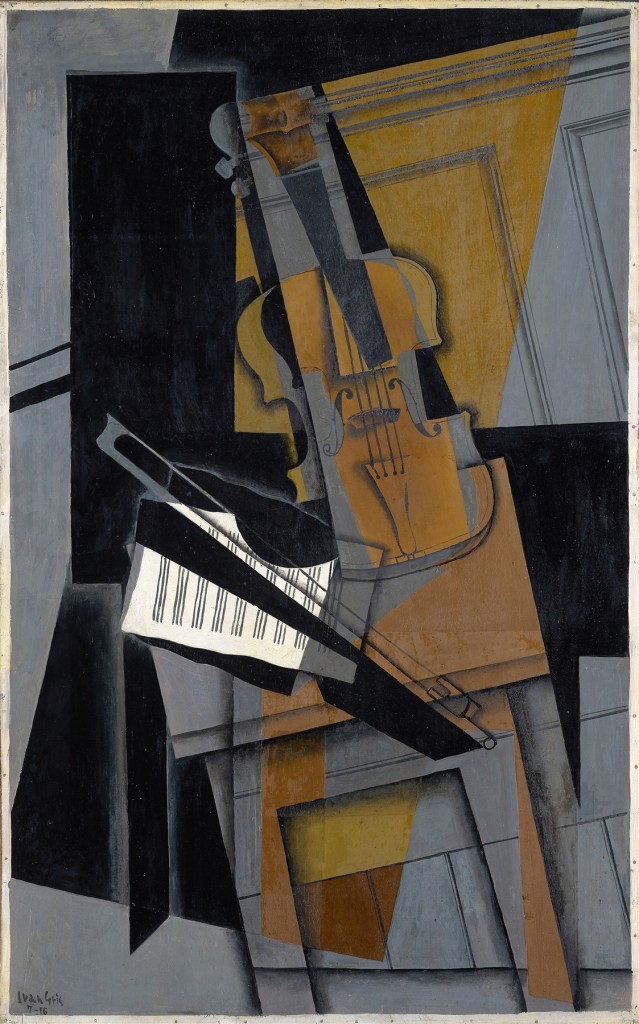

The Violin (1916) by Juan Gris How to sum up up these six masterpieces, all performed in the first two years of the ISCM (1922 and 1923)? If they can be said to be “about” anything, let’s just say they are explorations of the autonomous individual as viewed from the inside. Intimate, heart-wrenching, honest testaments from a time when everything was being questioned, nothing was certain. Six wagers on the human (non-religious) soul, whatever that is, played on one of the most perfect of objects ever created by human hands: the violin.

-

Mahler steals a march… or maybe not

Massed high woodwinds, a barrage of brass in lockstep, batteries of snare-drum-heavy percussion: the soundscapes of Mahler’s symphonies are pervaded by the specific sound-world of the Austro-Hungarian military wind band, and dominated by the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic tropes of the military march in particular.

There is hardly a Mahler symphony – and first movement in particular – that does not have a military march, or its morbid cousin, a funeral march, at its heart, often transformed into something more ambivalent. Like Mahler’s own multi-layered identity as an Austrian Jew (who later converted to Christianity), brought up in a German-speaking enclave within the Czech-speaking borderlands of Bohemia and Moravia, his music conveys complex layers of meaning, so that the military origins of much of his music is not always obvious.

And for those of us who grew up with Mahler’s music, we miss the visceral living connection to military music that his early audiences must have felt, particularly those living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where the Sunday morning band concert in the park was a regular event.

The marches were as difficult to tell apart as men in uniform. Mostly, they began with a drum roll, contained the accelerando of the tattoo and an outbreak of hilarity from the winsome cymbals, and ended with a rumble of thunder from the great side drum – the brief and cheerful storm of a marching tune… A pleasant and musing smile came to the faces of the listeners, and the blood quickened in their legs. Even as they stood still, they had the feeling they were marching.

from The Radetzky March, Joseph Roth, trans. Michael HoffmannUntil recently, such written descriptions – evocative though they can be – were the closest most of us could get to the original experience of this music as performed in Mahler’s time. But now, with the benefit of online archives (such as the evolving YouTube collection of Radiomuseum Hardthausen) we can hear recordings made before the First World War of just the sort of music that the composer and his contemporaries grew up with.

Listen to this march, recorded when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was still very much alive by the band of the Royal and Imperial Landwehr Regiment Nr. 1, Vienna, followed by an excerpt from the first movement of Mahler’s Third Symphony and you’ll hear the connection.

Here’s the Mahler:

When I first heard the military band recording, I thought that I had possibly made a minor musicological discovery: the first theme of the march is strikingly similar to Mahler’s theme. Could he have “borrowed” it?

But the dates don’t match up. I can’t find a composition date for the march (Oberst-Karreß-Marsch or Colonel Karress March), but when Mahler was composing his symphony between 1893 and 1896, the composer of the march, Jaroslav Labsky (1875-1949, born in Bohemia, about 90km from Mahler’s birthplace), was still a student at the Prague Conservatory.

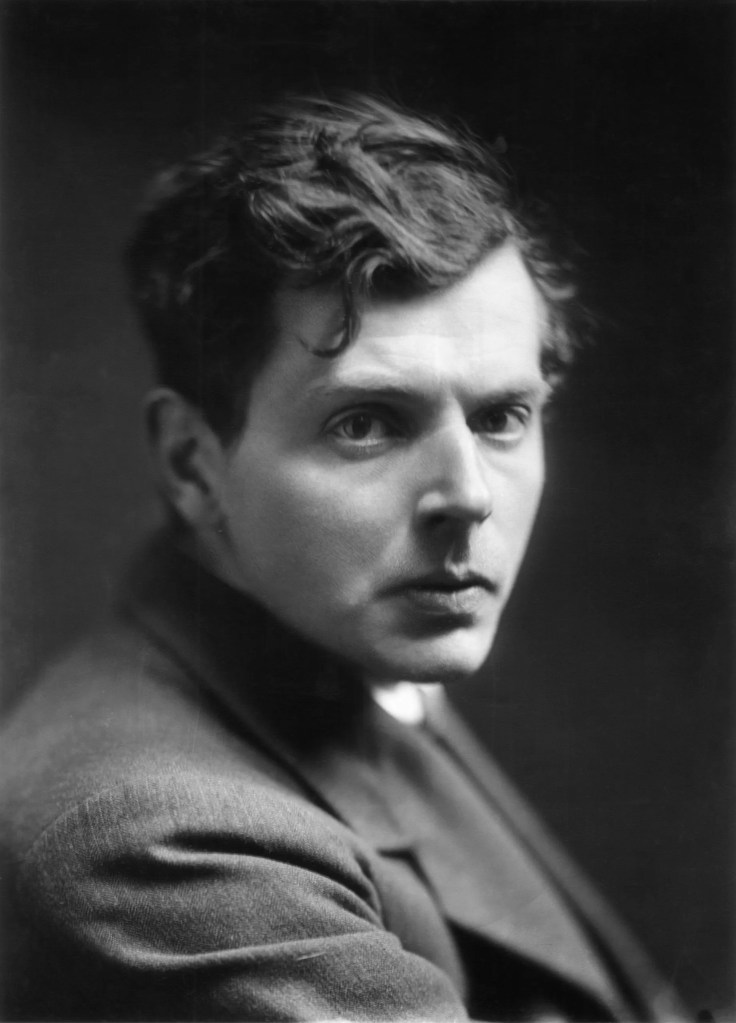

Jaroslav Labsky

Gustav Mahler Of course, the influence might have been the other way round, but I think it’s more likely that both composers were fishing in the same water – creating music from the library of sounds that were all around them.

Here’s another example from the same symphony. Not exactly military music, but definitely music of the borderlands: geographically, the southern borderlands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (see map below) where the nationalist struggles for independence of the Southern Slavs were to become the flashpoints that ignited the First World War; and musically, the overlapping borders between military, klezmer, and Balkan folk musics.

This is the posthorn solo from the third movement of the Third Symphony (played here on the flugelhorn, which highlights the parallels). Let’s listen to the Mahler first.

And now this flugelhorn solo with accompanying orchestra, recorded in about 1910 – a Serbian folksong about Stefan Dušan, the medieval Emperor of the Serbs, Greeks, Albanians, and Bulgarians (“Hear, Tsar Dušan, thy army calls for thee”).

The similarities in mood, melodic shape, accompanying lines in thirds, and simple underlying sustained harmonies can be clearly heard.

Mahler was a collector of sounds and his symphonies are, to some extent, vast aural collages of the sprawling empire, containing sounds that could be heard by any of its citizens, whether in a provincial town or an alpine valley. And, despite his reputation as a control freak, both as composer and conductor, he was, above all, a great listener.

Ethnographic map of Austria-Hungary (1896). Source: Diercke Schul-Atlas für höhere Lehranstalten, Braunschweig, G. Westermann, 1896. Postscript

Following some stimulating comments on this post in the Facebook group, Gustav Mahler Forum, from Joel Lazar and Igor Tomaszewski, I would like to share two of their suggested links.

The first is a video of the first movement of the Third Symphony in an arrangement for military band played by The President’s Own U.S. Marine Band. As well as demonstrating some wonderful playing by this elite wind band, it shows – in reverse, if you like – the military band origins of this music.

The second video is an introduction to the Fifth Symphony by the conductor, Iván Fischer. He touches on the military aspects of the first movement, as well as to other elements of the Austro-Hungarian musical soundscape, including the integral Jewishness of many of Mahler’s melodies.

-

My time with Strauss

Richard Strauss was born in June 1864. I was born in June 1964. In a blog series about recordings made 100 years ago, that chronological nicety gives me a little thrill, as, with a stretch of imagination, I can put myself in Strauss’s polished shoes in 1922. (Though, unfortunately, I don’t have the Mercedes. And the photo’s from 1924, but never mind.)

Readers will have to forgive a bit of self-indulgence in this post as I’m going to write about my own relationship to Strauss’s music. As the last post in this series it’s good to take stock: the idea was to listen back to the music and culture of a single year – 1922. I’ve been amazed at the variety and quality of the recordings, and it has given me a clearer insight into the way recordings are not like photographs: yes, they capture a specific moment, but they also often contain an imprint of style and tradition from an even earlier time. The project has also given me a new appreciation of historical time. My theory is that as we get older, we can paradoxically feel closer to eras further back. I now have personal memories of 1972 – 50 years ago, so a further 50 years back doesn’t seem so far away.

I would describe my critical stance to the music of Strauss as ambivalent. For me there’s often an inexplicable hollowness at the centre that no amount of pre-Hollywood lushness or extraordinary technical mastery can fill. But just occasionally, I have to give in. As here, in this early song, Morgen! (“Tomorrow”, 1894) where time stands still: “And tomorrow the sun will shine again…”

In this hybrid version (neither voice and piano, nor orchestral), the solo violin (uncredited here) sustains the melody beautifully with generous portamenti, while – as often in Strauss’s hero Wagner – the voice is almost incidental. But what a voice: the young Richard Tauber, who, in 1922, signed a five-year contract with the Vienna State Opera where Strauss was Musical Director.

In his symphonic poem Don Juan (1888) the 24-year-old composer was even closer to the Wagnerian aesthetic, this time revelling in the ecstatic soundworld of the Bacchanale from Tannhäuser or the Act 3 Prelude from Lohengrin. Certainly, those repeated wind triplets accompanying the main violin melody, bracket together Don Juan with the Lohengrin Prelude for clarinettists who wish they had as fast a tonguing technique as their woodwind colleagues.

The 1921/22 season marked Strauss’s rehabilitation in the USA and Britain following years of anti-German sentiment. After a successful American tour, Strauss stopped in England on his way home for concerts and recording sessions with the London Symphony Orchestra. (There’s an interesting interview with the composer in the Guardian archives, published four days before the present recording.)

One of the remarkable things about this record is that it was made at all, bearing in mind the recording conditions of the time. The reduced orchestra, with no more than 20 strings (only 6 first violins!) crowds claustrophobically around the recording horn, as this ghostly low-fi photo of the session shows:

The low-frequency sounds of the double bass were notoriously difficult to reproduce in early acoustic recording, so here – as in most early jazz recordings – a tuba is added to strengthen the bass line. There must have some very competent and agile tuba players around at the time, who would have been able to name a decent fee for their services.

Despite – or perhaps because – of these limitations, the recording has an air of irrepressible energy – even desperation – about it. And the feeling of being trapped in a small room with no escape route is not necessarily an inappropriate reaction to being in the presence of Strauss’s eponymous seducer.

From seducer to seductress, we now turn to Strauss’s sensationalist opera of 1905, Salome – the work that held a distorted mirror up to bourgeois decadence and – along with its successor, Elektra (1909) – pushed the dissonant boundaries of musical expressionism to the very edge, and from which Strauss seems to have spent the rest of his composing career recoiling. Although, it must be said that the Dance of the Seven Veils is the least controversial part of the opera, musically speaking: more Sherezadian exoticism than Munchian existential angst, even though it was the scene that got the censors hyperventilating in the early days.

I associate this opera with my own personal angst as, in my early years playing with Welsh National Opera, I got one of those pulse-racing phone calls telling me that the first clarinet was ill and could I “sit up” and play principal clarinet in the opening night of Salome? It was just before the dress rehearsal so I got one run-through and then it was curtain up. The part is quite knotty, to say the least – the opera starts with a slithery scale on the clarinet, containing the harmonic seeds for the rest of the piece, and from there on there’s nowhere to relax. I have no memory of how well I played, only that I survived and – unlike John the Baptist – kept my head.

Listening to this recording straight after the London Don Juan, it is striking how much more balanced and blended the Philadelphia orchestral sound is. This is no doubt partly due to Stokowski’s intense interest in recording techniques and orchestral layouts (he is credited with establishing the now usual seating of violins 1 and 2, violas, and cellos, going left to right). There is a direct line from this recorded sound to the innovations in high fidelity and early stereo in later decades, and also – musically – to the neo-Straussian film scores of Korngold and his successors, as well as to the remarkable cartoon soundtracks by Carl Stalling and others. This, of course, came full circle in 1940 with Stokowski’s key role in Disney’s Fantasia.

Der Rosenkavalier was only 11 years old when the following recording of the waltz sequence was made in London – the day after the Don Juan above. The opera marks Strauss’s step away from the edge of the abyss of musical psychosis towards the more comforting distractions of 18th-century farce. Just as Wagner had written his 5-hour Der Meistersinger as a little light relief from the woes of mythological archetypes, so Strauss wrote his 4-hour sit-com that ends as a rom-com, showing that he could do comedy too (which of course he had already demonstrated orchestrally in Till Eulenspiegel and Don Quixote).

The addition of the tuba on the bass line this time brings the music perilously close to the sound of a Bavarian oom-pah band, and I wonder whether Strauss had a twinkle in his eye when he first heard it. After all, it’s not totally inappropriate for the Act 3 setting of “the back room of a dingy inn” (as the Met synopsis puts it), given that 19th-century waltzes are also totally anachronistic for a plot set in the 1740s.

Underlying the comic plot-line of a lecherous oaf being given his come-uppance, the opera has a more wistful message, dealing with the inevitability of the passing of time in the lives of the characters. The most effective production I have seen was in Helsinki some years ago, where, with the help of a revolving stage, the whole set gradually changed throughout the opera, but so slowly as to be imperceptible – quite literally a moving interpretation of the flow of time.

I’ve played in quite a few performances of Der Rosenkavalier and – like all Strauss – it is immensely satisfying to play: difficult, but so well written for each instrument that it’s worth the effort. Just like the couple of Alpine Symphonies I’ve played in, you struggle to get up the mountain, but the view from the top is glorious. My first ever work with Welsh National Opera was Der Rosenkavalier in 1994, playing in the off-stage waltz band. The music occurs in Act 3 – quite late in the opera, and I have the memory of hearing the start of the performance on the car radio on my journey from London to Cardiff as it was being broadcast live; quite a disconcerting experience, providing the material for quite a few performance-anxiety dreams in the years to come.

1922 is pretty close to the midpoint of Strauss’ composing career. It’s interesting just how many trajectories there are in the output of different composers: the short-lived firework (Mozart, Schubert), the creator who simply retires when all is said (Sibelius), the late developer (Janaček), the constant developer (Beethoven, Verdi). In my view, apart from a very few exceptions, Strauss had scored all his best goals in the first half. And I’m not even going to get into the controversies surrounding his later accommodation with the Nazi regime. Maybe, the last word should be left to the Marschallin, courtesy of librettist Hugo von Hoffmansthal, in Act 1 of Der Rosenkavalier:

Time is a strange thing. While one is living one’s life away, it is absolutely nothing. Then, suddenly, one is aware of nothing else. It is all around us – inside us, even! It shifts in our faces, swirls in the mirror, flows in my temples. It courses between you and me – silent, as in an hourglass. Oh, often I hear it flowing, irrevocably. Often I get up in the middle of the night and make all, all the clocks stand still.

[Richard Strauss: Morgen. Richard Tauber, tenor. Violin, piano: anonymous. Recorded Berlin, 1922.]

[Richard Strauss: Don Juan. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer. Recorded Clerkenwell Road Studio, London, 18 January 1922.]

[Richard Strauss: Salome’s Dance. Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski. Recorded Camden, New York, 5 December 1921.]

[Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier, Waltz Sequence. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer. Recorded Clerkenwell Road Studio, London, 19 January 1922.]

-

Do it Again… and again… and again… and again

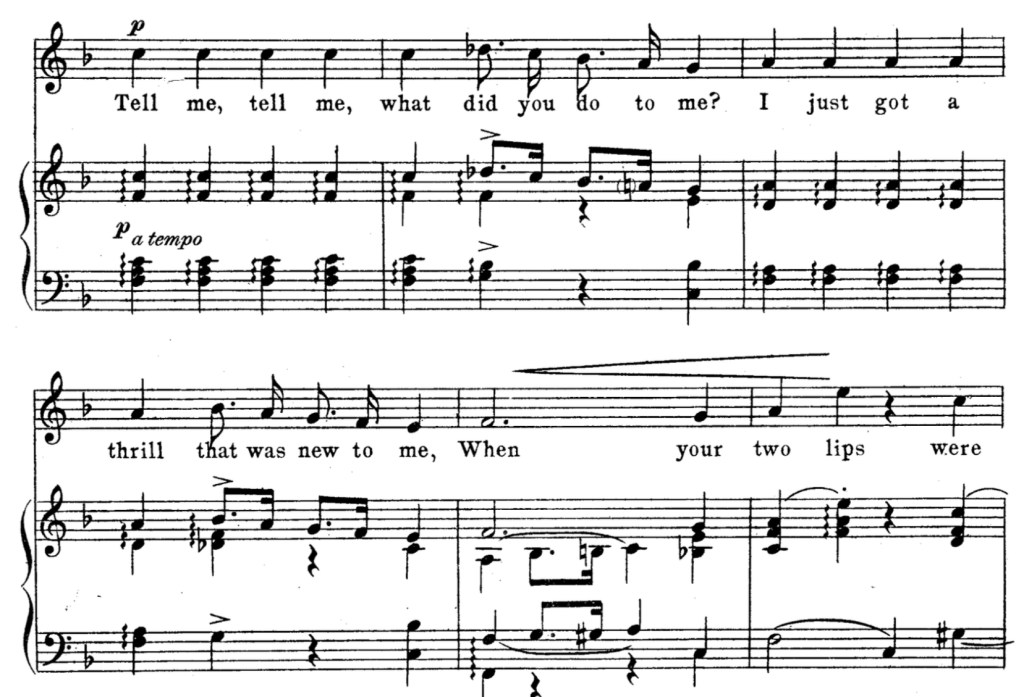

The 23-year-old George Gershwin was already a prolific composer by the time The French Doll opened on Broadway in February 1922. The musical comedy ran for 120 performances, but its lasting legacy was the single song that Gershwin wrote for the show: Do it Again, with racy lyrics by Buddy de Silva.

The song already has the touches of Gershwin’s later classics with its repetition of deceptively simple melodic phrases, and an underpinning of subtle harmonic touches that, if slowed down, could be by Tchaikovsky or Sibelius:

Gershwin: Do it Again

Tchaikovsky: 6th Symphony. movt. 2 The speed of production in the New York music arranging, publishing, and recording industries matched the assembly line of the Ford Motor Company in the 1920s, and in the space of of a few weeks and months the tune had been released on record by multiple dance bands.

Here are four of those hot-off-the-press versions, each followed a by a few comments on some of their noteworthy features:

Joseph Samuels was a busy bandleader and multi-instrumentalist about whom not much is known. My guess is that he is the soloist playing the melody at 0:29. I’m still not absolutely convinced that this is a clarinet, rather than a Sidney Bechet-like soprano saxophone. But there is one little touch that shows the player’s Jewish background, whoever he was – an unmistakable klezmer lick at 0:33.

This is the only one of the four recordings featuring a vocalist – the vaudeville artist Arthur Hall at 1:31. A man singing the lyrics originally written for a woman emphasises that the song’s saucy subject is really a projection of what a man would like to hear a woman say!

Ernest Hussar’s orchestra was the resident dance band at Hotel Claridge, New York. This version starts with a similar score to the previous version, but then goes a little off course, with a nice little modulating excursion at 2:15, and a classy coda from 3:05, but nothing to shock the well-dressed hotel guests.

Paul Whiteman’s version is unsurprisingly suave and sophisticated, and performed with precision and discipline. As with all these fox-trot arrangements, the rhythm is taut and over-dotted – the almost military spring-loading in the staccato articulations of trumpets and banjo has not yet given way to the more relaxed swing rhythms of jazz.

This is the only version to experiment with extended sections in minor keys (at 1:09): F minor, then G minor, followed by a chorus in G major, before returning home to F major. Then, just before the end, there is a cheeky diversion to a distant A major (2:59) – a forgivable bit of showing off from a clever arranger.

I’ve saved my favourite one to last. We’ve come across Harry Raderman before – as a trombonist in some classic klezmer. Here, he is leading his dance band from the stand of his laughing slide trombone in an up-tempo version of the Gershwin tune. This arrangement’s got a bit of everything: even a duet for glockenspiel and kazoo – not something you hear every day (1:20).

And it’s just as clever as the Whiteman (which was recorded 6 days earlier): extended modulations to B flat major and G major, followed by some nice classical quotation at 3:11, whose source I can’t put my finger on (answers in the comment box below please).

For the final course (at 3:20) we’re treated to a serving of dixieland improvisation, giving this version a spirit of spontaneous joy that doesn’t always come across in a recording studio.

I defy anyone to listen to this record without a smile on their face!

[George Gershwin: Do it Again. Joseph Samuels’ Music Masters. Vocal Chorus by Arthur Hall. Recorded 1922]

[George Gershwin: Do it Again. Ernest Hussar and his Orchestra Hotel Claridge, N.Y. City. Recorded 1922]

[George Gershwin: Do it Again. Paul Whiteman Orchestra. Recorded New York, 28 March 1922]

[George Gershwin: Do it Again. Harry Raderman´s Orchestra. Recorded New York, 3 April 1922]

-

String quartets, poetry, and cups of tea: Frank Bridge and Ivor Gurney

British classical music in the early twentieth century was dominated by the teaching of an Irishman: Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 – 1924), Professor of Composition at the Royal College of Music since its founding in 1883, and Professor of Music at Cambridge University since 1887, where he established Music as an academic subject requiring a three-year degree.

Draw up a list, haphazard, of the most prominent British composers of recent years, in every branch of writing, and you will find that it consists principally of Stanford’s pupils. Let me enumerate just a few of of the best-known names: Charles Wood, Hamish MacCunn, Walford Davies, Coleridge Taylor, William Hurlstone, Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, John Ireland, Frank Bridge, Rutland Boughton, Cyril Rootham, Nicholas Gatty, Martin Shaw, Edgar Bainton, James Friskin, Herbert Howells, Ivor Gurney, George Butterworth, Rebecca Clark, Arthur Benjamin, Arthur Bliss, Eugéne Goosens.

Thomas Dunhill: Proceedings of the Musical Association, 1926-1927Just two of these names concern us here: Frank Bridge and Ivor Gurney. Stanford – as composer and teacher – was a bulwark of Victorian conservatism (Debussy, Richard Strauss, and even Delius were regarded as dangerous radicals by the professor), and his predominance in musical life for so long is part of the reason that British music largely bypassed European modernism. But that’s not the whole story. The First World War shook things up in Britain, just as much – if in quieter ways – as in the more revolutionary parts of continental Europe.

Even these two light string quartet miniatures by Frank Bridge – arrangements of two popular English songs – show both sides of the musical reaction to the Great War: an aching nostalgia for a pre-war idyll combined with hints of a more experimental and disorienting use of harmony of the kind that might have made Sir Charles a bit twitchy.

Frank Bridge

Ivor Gurney As Bridge was finishing the score of these pieces in May 1916, the 25-year-old poet and composer Ivor Gurney was marching with the 2nd/5th Gloucester Regiment towards the fields of Flanders. Later in that year, Gurney was one of the “lucky” survivors of the Battle of the Somme, but a year later he inhaled poison gas near Passchendaele and was sent to a series of hospitals back in Britain. Eventually – in October 1918 – he was discharged from the army with “deferred shell-shock”.

There’s little doubt that Gurney’s wartime experiences exacerbated a pre-existing mental health problem, which led to suicide threats and erratic behaviour. In September 1922, following four prolific years of composition and poetry, he was committed to an asylum in Gloucester, and in December he was moved to the City of London Mental Hospital (based in Dartford, Kent) where he spent the rest of his life (he died in 1937).

Gurney continued to write music and poetry and, though justly famous for his war poetry and evocations of his beloved Gloucestershire (the title of his first published collection, Severn and Somme, sums this up), he also gives us occasional glimpses into his everyday life. One such poem is Masterpiece – a fascinating insight into the composition of a string quartet in a fairly lighthearted tone (the title is surely tongue-in-cheek) – in which he links poetry and music: two equally important art forms for Gurney. The poem has been dated to November-December 1924: Gurney marked the manuscript “27th month” (i.e. of incarceration).

Ivor Gurney isn’t unusual for a poet in sometimes using a sort of private language – turns of phrase where only the poet really knows what is meant, or references to things or places that have particular significance to the writer, but that we as readers have to guess at and interpret, a bit like being a detective at a crime scene. This is to say that what follows is a personal interpretation and is not to be taken as a definitive reading.

The black humour of the poem lies in the frustration felt by the creative artist who can’t stop creating, but knows that his work will not be read or performed: a String Quartett nobody in the world will do.

We witness the process of composition – from the flashes of inspiration to the weeks-long working out of sketches, trying not to be distracted by the non-understanding neighbours and people around him, including, possibly, the nursing staff calling when it’s time for tea: Half-past two? Time for tea… Half-past, half-past two…

The choice of Schumann as the composer/critic whose opinion no-one is interested in is surely not arbitrary: Robert Schumann is well-known for also spending his last years in a mental asylum. There is a self-awareness in this poem that is quite extraordinary for someone deemed not fit to manage in the outside world.

In the second part of the poem, Gurney pokes fun at the London literary (and by implication, musical) establishment. Here he conflates poetry and music, complaining that, even if the work did receive a performance, it would not get critical approval – either too serious, or not serious enough. (Weltmuth – a made-up word sounding pretentiously German – “world courage”; Sarsparilla – “sarsaparilla” – a herbal substance or drink, possibly administered in the hospital.) Sarsparilla/gorilla provides a cheap rhyme, but also introduces a childish surreal element that seems intended to provoke.

There is a very modern use of stream-of-consciousness word association going on here – an almost random choice of words and rhymes, that highlights the workings of the unconscious mind in quite a knowing way, I would suggest.

When the composer gets the audience’s indifference he was expecting, he is left to read his book of Shakespeare in the early hours (when the dim East shows blind) and turns to drink (tea, or something stronger?).

Word association continues with the “found poetry” of brands of tea: Lyons and Lipton, though the mention of the London String Quartet could also connect with Lyons’ Corner Houses – restaurants where live music was part of the experience (the quartet also gave “Pops” concerts in wartime London – quite possibly including the Bridge miniatures in their repertoire).

But there is one final possibility that I will put forward. It is known that Gurney had access to a gramophone in the asylum and even that record companies donated records to the institution. Could the final line refer to this very recording of the London String Quartet? Or – see… how the two tunes into one English picture came linking. And could the choice of the word “linking” (to rhyme with “drinking” and “thinking”) be a playful acknowledgement of Gurney’s fellow composer, Frank “Bridge”? Who knows?

Footnote: Gurney scholar, Dr Philip Lancaster, has informed me that at 7.30pm on 17th December 1924 the London String Quartet made a radio broadcast on the newly formed BBC, so this could also have been a prompt for the poem, or at least for particular references.

[Frank Bridge: Two Old English Songs – Sally in our Alley/Cherry Ripe. London String Quartet. Recorded New York, 13 March 1922]

-

“You’re in the right church, but in the wrong pew”

This is a woman with attitude. This is a band with attitude. Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds were launched into the world of recorded music as the real sound of African American jazz in the early 20s after several years of an often fairly tidied up version in more respectable arrangements by mostly white musicians. The release of Crazy Blues in 1920 is widely regarded as the first blues song recorded by an African American artist.

Mamie Smith This 1922 recording of Don’t Mess With Me is raw organised chaos. There’s no obvious band leader apart from Mamie Smith herself, riding the waves of sound like the figurehead of a ship on stormy waters. At the age of 41 she must have been twice the age of most of her band members and there’s definitely no messing with her musical authority.

The sound of this band of improvising musicians is remarkable: wild and dangerous, with its instability emphasised by the lack of a real bass instrument, though the trombone and baritone sax vie with each other to interject fragments of low growls and barks – the baritone possibly played here by a 17-year-old Coleman Hawkins who had just joined the band. (Smith had tried to recruit him a year earlier, but his family said he was too young.)

We’re listening to jazz history in the making. Hawkins went on to become one of the great tenor saxophone soloists, and the trumpeter James ”Bubber” Miley (just 19 years old here) was soon to provide an important ingredient as part of the Duke Ellington sound.

And what’s that high wailing noise flying around all over the place? Presumably it’s the violinist doing his wild and crazy thing, duelling while balancing on a high wire with his clarinettist colleague.

Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds 1922. Left to right: unknown, Bubber Miley,unknown, unknown, Mamie Smith, Coleman Hawkins, unknown, unknown. Now, when the trumpets sounded, even the saxophones, then the multitude arose, two by two and stood upon the floor and shook with many shakings.

from Zora Neale Hurston: The Book of Harlem (1927)Mamie Smith’s recordings are an essential part of what became know as the Harlem Renaissance: that cultural flowering of African American art and literary life in the 1920s, celebrating and questioning the role of black culture in society and politics. Not only did the mass migration of African Americans from the south to the north, and specifically to Harlem in New York, lead to a flourishing of art, but it also provided a mass audience for “ethnic” jazz records, something that OKeh Records recognised when they took on Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds.

Smith’s singing in Don’t Mess With Me is a rebuke to the prevalent sexism of the time, portrayed so well in the short stories of Zora Neale Hurston:

… Jim flopped into a chair and held forth at great length on the necessity of keeping wives in their places; to wit: speechless and expressionless in the presence of their lords and masters and cited several instances where men had met their downfall and utter ruin by ill advisedly permitting their wives to air their ignorance by talking. His audience, composed entirely of males, agreed with him.

from Zora Neale Hurston: The Conversion of Sam (1922)Part of the strength of this song is that, though the subject matter is often quite violent, the text (credited, like the music, to Sam Gold) is sublimely witty, with some great rhyming couplets:

If I land on you (oh Lord),

Next time people talk to you, it’ll be through a Ouija board

[Note: spiritualism and contacting the dead via Ouija boards were at their heyday in the 1920s.]And of course it’s not just the words and music, but how they are delivered that counts. And no one could deliver this gritty song of revenge, mockery, and female power better than the stupendous Mamie Smith, with her Jazz Hounds yapping at her heels.

The gifts divine are theirs, music and laughter:

from Claude MacKay: Harlem Shadows (1922)

All other things, however great, come after.[Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds: Don’t Mess With Me (Sam Gold – composer and lyricist). Recorded New York, December 1922]

-

Beethoven and Rilke – “existence is still enchanted”

By 1922 the 10-inch 78 rpm disc was pretty much established as the norm for commercial recording. The 3 minutes or so that could fit on one side set the template for pop songs that continues to this day. Classical recordings were often released on 12-inch discs, which allowed for an extra minute or two, but it meant that most of the early recorded repertoire of classical music was restricted to short pieces or movements – often abridged – from longer works (though there are exceptions: the first complete opera recording – Verdi’s Ernani – was released in 1903 on 40 single-sided discs, which must have provided healthy exercise for its armchair listeners).

This recording of Beethoven’s first string quartet was one of the earliest complete recordings of a whole quartet – movements recorded separately on different dates, but with no cuts, and released on 7 sides. The Catterall Quartet was one of England’s finest chamber ensembles, led by the leader of the Hallé Orchestra (and later the first leader of the newly-formed BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1929), Arthur Catterall. This is quartet-playing at its best: equality of the four voices, flexibility in pulse, and effortless virtuosity when required.

Catterall Quartet. Left to right: Frank S. Park viola, John S. Bridge 2nd violin, Arthur Catterall 1st violin, Johan C. Hock ‘cello. Credit: Special collections Queen’s University, Belfast MS14 Meanwhile, in a chateau in Switzerland the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (born in Prague, 1875) was on a creative high. 1922 was the year in which he finished his monumental Duino Elegies (begun in 1912) and – almost as an afterthought – wrote in the space of a few weeks the 55 poems that comprise the Sonnets to Orpheus.

Rainer Maria Rilke, c.1923 The sonnet cycle is an outpouring of songs in praise of creativity. And there is much about music and the importance of deep listening to the world as a way of finding our true selves. Although Rilke’s reputation has waxed and waned over the years (his extreme sensitivity and his detachment from ordinary life during his sojourns in the castles of the Alpine nobility can seem a bit precious), I would argue that just like we needed the hippies of the 60s or the punks of the 70s to shine a light on the hypocrisies of the modern world, so we still need the poetry of Rilke to remind us what is really valuable beyond our normal everyday concerns, or rather, to see what is valuable when we pay close attention to everyday things.

It can safely be said that Rilke would not have been a big fan of some of the more commercially successful recordings featured in this blog, especially as many of them were made in the USA. In a letter of 1922 he lets rip on the shallowness of much American culture:

Now there come crowding over from America empty, indifferent things, pseudo-things, dummy-life… A house, in the American sense, an apple or vine, has nothing in common with the house, the fruit, the grape into which the hope and pensiveness of our forefathers would enter… The animated, experienced things that share our lives are coming to an end and cannot be replaced. We are perhaps the last to have known such things.

from Briefe aus Muzot, trans. J.B. LeishmanWhile this outburst can easily be dismissed as the snobbish old-world ramblings of someone fighting an already lost battle against new-world modernity, it must be said that a culture that produced the empty fakery of a Trump presidency a century later might just be enough evidence to show that Rilke was not entirely wrong.

And if we remove the controversial cultural nationalism from the argument, maybe it’s worth attending to what Rilke is saying: that our relationship to the world around us needs to be deep-rooted and we need to listen, and respond.

In an extraordinary essay on Primal Sound, written in 1919, Rilke reveals his fascination with early recording technology: how a stylus on a wax disc can both record sound and reproduce that same sound. He then makes a quite complicated analogy, which I think can be summarised by saying that a creative individual’s relationship to the world is symbiotic or reciprocal – both receiver and transmitter.

And Beethoven was perhaps the ultimate receiver/transmitter: inhaling the spirit of the age and then practically launching the nineteenth century with this quartet (written 1798-1800, published 1801), with its adagio second movement providing the source of all future adagios up to Bruckner and Mahler and beyond.

What is it about this performance, and others like it, that makes us want to listen through all the limitations of early sound recording with all that excess surface noise? Yes, it’s partly our fascination with the traditions from which the musicians come. And there’s also that thrill of “being in the room” with the music being produced a 100 years ago – a sort of time travel. But isn’t it also that these musicians did not grow up like us surrounded by recorded music, whether we want to hear it or not? ”Live music” for them was just music. They were “perhaps the last to have known such things”.

One of Rilke’s sonnets seems especially relevant here. It can also be read as a prescient comment on the age of the smartphone, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, but in this context, Beethoven can be heard in the echo.

Rilke: Sonnets to Orpheus, Part 2, No. 10, trans. Robert Hunter [Beethoven: String Quartet in F major, op. 18, No. 1. The Catterall Quartet. Recorded Hayes, Middlesex, 1922 & 1923]

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.