-

Modernism in miniature?

Here we are at post no. 12 in this series on recordings of 1922 and there’s been little mention of the m-word. 1922 is often seen as a crucial year in the history of Modernism – the year that saw the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. And both writers were encouraged by the poet Ezra Pound – a fetishist of “isms” (most notoriously, fascIsm), who designated 1922 as Year Zero.

Although 1922 might have been a key year for literary innovation, it doesn’t fit so well for music. Several groundbreaking works of musical modernism appeared somewhat earlier: Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in 1912 and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913, for example. And in the context of this blog series, which deals with the commercial realities of the early years of producing and selling records, very few of these works made it into a recording studio until several years later.

So how about we listen to this 3-minute “novelty rag” as a representative example of popular-culture modernism?

Instead of the bloated late-Romantic forces involved in Edgar Varèse’s Amériques – 142 players required for the original 1921 version – as an evocation of the modern urban world, why not a single piano player distilling the individual’s disoriented exhilaration at being swept up by the city that never sleeps?

Times Square, New York, 1922 (Note the advert for the oriental-themed Broadway musical, The Rose of Stamboul – see earlier post.) Recent posts (here and here) have discussed the musical flexiblity of human movement – dances from an earlier age. But now, the new dances of the 20s have a frenetic regularity, and even if novelty rags were already a bit passé by 1922, if you were an American equivalent of a Bright Young Thing and you had your finger on the pulse, it was likely to be the pulse of an internal combustion engine.

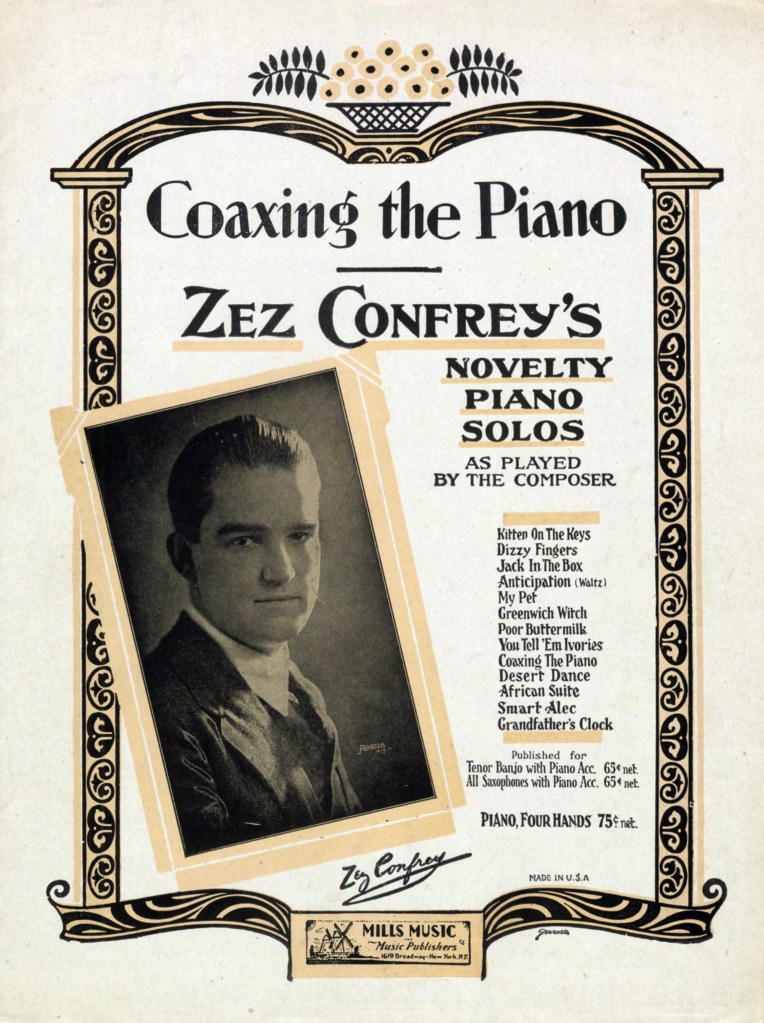

The composer and pianist Zez Confrey recorded many piano rolls. This piece – and others like it – is almost the player-piano process in reverse: sounding like it’s written for an automatic electrically-driven machine, but also able to be attempted by human fingers on an old-fashioned piano. The sheet music that was sold for amateur pianists – with its performance note above the title: “This number is very effective when played quickly and staccatto [sic]” – must have been a challenge that only the most proficient were ever likely to meet. (The version for piano, four hands was possibly slightly more achievable.)

If we need confirmation of Zez Confrey’s position at the cutting edge of popular music, we just need to have a look at the advertising for the concert that featured the famous premiere of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in 1924, where Confrey gets top billing:

And if Gerswhin’s experiment pushes jazz towards symphonic form, Confrey has gone in the opposite direction in this recording: a three-minute metropolitan microcosm of early 1920s New York, engraved in shellac on a 78rpm disc.

[Coaxing the Piano: Zez Confrey (composer and piano). Recorded New York, approx. November 1921, released 1922]

-

Naftule Brandwein and Joseph Roth: sketches of a lost Europe

This is the music of borders. Or the crossing of borders.

The great klezmer clarinettist, Naftule Brandwein crossed the maritime border of the USA in April 1909 to join his brother Israel who was already living in New York. But his musical journey had begun much earlier – from birth in fact, as he was born into a musical dynasty of klezmorim in 1884. In the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe, music was a hereditary profession.

Following the ineluctable law of the East, every poor man, including therefore the musician, has numerous children. In the musician’s case this is both good and bad, for the sons will go on to be musicians in turn, and form a “band”, which, the bigger it is, the more money it will earn. The more people who bear the family name, the more the band’s renown will grow. Sometimes a later descendant of this family will go out into the world, and become a celebrated virtuoso. There are a few such now living in the West; it would serve no purpose to name them. Not because it might somehow embarrass them, but because it would be unfair to have their greatness confirmed by any talented descendants.

Joseph Roth, trans. Michael Hofmann, The Wandering Jews (1926)What a gift for words Joseph Roth had! And what a delight to discover that one of my literary heroes and my favourite klezmer musician were born 10 years apart and only about 50 miles from each other, near Lemburg (now Lviv) in Austro-Hungarian Galicia (now part of Ukraine), though thoughts soon turn to the subsequent catastrophic history of Jews in this part of Europe as well as to the current daily news of war in the region.

Naftule Brandwein with his Albert system C clarinet

Joseph Roth; Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris, Leo Baeck Institute, c. 1926 Galicia (not to be confused with the similarly named region of northern Spain) is one of those resonant names – like Bessarabia and Bukovina – that summon up a lost world of East European Jewry, as well as a centuries-long era of constantly shifting borders, when inhabitants found themselves suddenly citizens of another state or empire – or were forced to move to a new place.

Map of Eastern Europe in 1900 with Galicia highlighted. The light red part of the Russian Empire shows the Pale of Settlement – the only area where most Russian Jews could live, but only in towns and in restricted trades and professions. Joseph Roth spent most of his adult life living out of a suitcase. Though he is best known for his masterly end-of-empire novel, The Radetzky March (note how the title uses a musical association to conjure up a lost age), the books that sit constantly on my bedside table are the collections of short articles that he wrote regularly for various European newspapers. These feuilletons – as they were known – were written in cafés and hotels around Europe, and they have an almost musical improvisatory quality as spontaneous observations of everyday life in the 1920s and 30s. As Roth wrote, “Only the small things in life are important”. Here is a sample from a sketch written in Berlin in 1922:

Sometimes a ride on the S-Bahn is more instructive than a voyage to distant lands. Experienced travelers will confirm that it is sufficient to see a single lilac shrub in a dusty city courtyard to understand the deep sadness of all the hidden lilac trees anywhere in the world…

A boy listens to a big phonograph on the table before him, its great funnel shimmering. I catch a brassy scrap of tune and take it with me on my journey. Torn away from the body of the melody, it plays on in my ear, a meaningless fragment of a fragment, absurdly, peremptorily identified in my memory with the sight of the boy listening.

Berliner Börsen-Courier, April 23, 1922 (trans. Michael Hofmann)Just a few months after Roth wrote these lines, Naftule Brandwein was making his first recording as a solo clarinettist in the Columbia studio in New York, starting his Doina with an improvised “fragment of a fragment”.

The doina is – like many klezmer forms – an adaptation (perhaps a “yiddishification”) of a musical form and style of a particular regional folk tradition. It is a semi-improvised solo over sustained chords, usually – as here – followed by one or two faster dances. It has much in common with the Turkish taksim, the slow lassú section of the Hungarian verbunkos, and its function as a slow introduction even recalls the recitative section preceding a classical aria. There is also a clear connection to the style of Jewish cantor recitation.

The specific regional form that klezmer musicians borrowed (no accusations of “cultural appropriation” please) is the Romanian doina. Here’s a good example:

[Doina played by Luca Novac on the táragató, most easily described as a wooden soprano saxophone (conical bore, not cylindrical like the clarinet).] For Brandwein’s doina, he has metaphorically crossed the Carpathian mountain range – the natural border between Galicia and Romania. He has also crossed the boundary between urban and rural. The Romanian doina is the music of shepherds – there is often an unwritten “story” in the music of a lament for a lost sheep, followed (in the fast section) by a celebration of its return. As it is unlikely that there were very many Jewish shepherds in Eastern Europe (agriculture was usually out-of-bounds to Jews), this is another example of the crossing of imaginary borders.

That was how things were back then. Anything that grew took its time growing, and anything that perished took a long time to be forgotten. But everything that had once existed left its traces, and people lived on memories just as they now live on the ability to forget quickly and emphatically.

Joseph Roth, The Radetsky March (1932)[Rumeinishe doina, Naftule Branwein (clarinet) and orchestra. Recorded approx. September 1922, New York]

-

Rhythm is life: Paderewski and the Art of Rubato

During these dark times in Europe my recent posts have dealt with music and politics, so who better to listen to next than one of the greatest musicians of his age who was also an international statesman and passionate advocate of the right of nations to determine their own future?

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (born 1860 in the Polish village of Kuryłówka – then in the Russian Empire as was much of Eastern Poland, now in Ukraine) campaigned for Polish rights during the First World War, and was considered such a unifying figure that he was appointed Prime Minister of a newly independent Poland. He attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and was one of the signatories of the Treaty of Versailles, managing to negotiate the resolution of complex border disputes with Poland’s neighbours to the south and east: Czechoslovakia, the Ukrainian People’s Republic and Soviet Russia. Following his short tenure as Prime Minister, Paderewski represented Poland at the League of Nations until retiring from active politics in 1922 to concentrate on music once more.

And it is musical matters that I want to turn to in this post, firstly noting how remarkable it is that the 61-year-old pianist managed to revive his exceptional technique so quickly after his years at the hot end of international politics.

The long-haired superstar, painted by Edward Burne-Jones in 1890, photographed in 1920, and caricatured by Ralph Barton in 1922. In his interpretation of Liszt’s arrangement of a song by Chopin, The Maiden’s Wish, Paderewski gives us a perfect example of the balance between precision and freedom that characterizes his playing. In an essay published in 1909 on Tempo Rubato the pianist gives a summary of his philosophy of rhythm. The opening paragraphs are worth quoting at length:

Rhythm is the pulse in music. Rhythm marks the beating of its heart, proves its vitality, attests its very existence. Rhythm is order. But this order in music cannot progress with the cosmic regularity of a planet, nor with the automatic uniformity of a clock. It reflects life, organic human life, with all its attributes, therefore it is subject to moods and emotions, to rapture and depression.

There is in music no absolute rate of movement. The tempo, as we usually call it, depends on physiological and physical conditions. It is influenced by interior or exterior temperature, by surroundings, instruments, acoustics.

There is no absolute rhythm. In the course of the dramatic developments of a musical composition, the initial themes change their character, consequently rhythm changes also, and, in conformity with that character, it has to be energetic or languishing, crisp or elastic, steady or capricious. Rhythm is life.

Paderewski goes on to correct one of the common misconceptions of rubato: that one should compensate for any slowing of tempo by subsequently speeding up, and vice versa. As he writes, “We duly acknowledge the highly moral motives of this theory, but we humbly confess that our ethics do not reach such a high level… The value of notes diminished in one period through accelerando, cannot always be restored in another by ritardando. What is lost is lost.”

He also notes that rubato is a typical feature of folk or “national” music: Polish mazurkas, Hungarian dances, Viennese waltzes. And this brings us back to the specific recording at hand – a folk-like song in the form of a waltz.

Paderewski’s waltz steps float above the ground – defying gravity in the way the best dancers do. Somehow, in this music, the human body has become weightless, until, in the quintessentially Lisztian second variation (at 2’31″), it has virtually sprouted wings, before being brought down to earth again towards the end of the third variation.

For anyone wishing to explore further, one YouTuber has very helpfully made a compilation of recordings of this piece made by four of Paderewski’s contemporaries. The four pianists are (note the complexity of their East European backgrounds):

- Leopold Godowsky (Jewish, born 1870 in Žasliai, then Russian Empire, now Lithuania)

- Josef Hofmann (Jewish, born 1876 in Kraków, then Austro-Hungarian Galicia, now Poland)

- Moriz Rosenthal (Jewish, born 1862 in Lemberg, then Austro-Hungary, later Lwów, Poland, now Lviv, Ukraine)

- Sergei Rachmaninoff (born 1873, near Novgorod, Russian Empire)

It is startling how diverse the different versions are. To my ears all four root their waltz steps more firmly to the ground than in Paderewski’s performance, and although all the pianists have phenomenal techniques, some of the fast passagework sounds merely virtuosic, rather than poetic.

But what is perhaps most striking is how free all the interpretations are, even to the extent of rewriting rhythms and adding extra notes. (Moriz Rosenthal’s version even has a whole section of newly-composed music.)

It’s easy to become misty-eyed with nostalgia for performing styles of the past, but maybe we have lost something valuable over the past hundred years (ironically, partly as a result of the prevalence of recorded music). It is notable that all five pianists considered here were also composers. That connection between creativity, composition (both spontaneous and written), and performance – something that is still integral to most other musical traditions – has largely been lost in classical music.

It’s not just in the world of politics that freedom is something that has to be continually fought for.

[Chopin-Liszt: The Maiden’s Wish, Chant Polonais Op. 74, No. 1. Ignace Jan Paderewski – piano. Recorded Camden, New Jersey, June 27, 1922]

-

On Being Hu(ber)man

If you’re a world-class musician at the height of your fame, and your country, or the country where you perform, commits crimes against humanity, what do you do or say?

If you want to take an ethical stance, there are essentially two alternatives: the Furtwängler option and the Huberman option.

As the Nazi Party tightened its grip on Germany in the 1930s, the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, Wilhelm Furtwängler, decided to stay in Germany, hoping that his musical art could somehow rise above the evil around him. The risk was that he and his orchestra would be used as a propaganda weapon to give Nazism a positive spin.

The Polish-Jewish violinist Bronisław Huberman, on the other hand, refused to play in Nazi Germany. As he wrote to a friend in 1933,

“I am a Pole, a Jew, a free artist and a pan-European. In each of these four character traits, I must see Hitlerism as my mortal enemy, I have to fight it with all the means at my disposal as my honour, my conscience, my reflection and my impulse dictate”,

Lesser Ury: Portrait of Bronisław Huberman, ca. 1916. The danger signs in Europe were clearly evident a decade earlier. In July 1921 Hitler became chairman of the National Socialist Party, which had previously announced that only those of “pure Aryan descent” could become members. And in October 1922 German fascists took heart from Mussolini’s March on Rome and subsequent coup d’état in Italy.

By the early 20s, Huberman was already politically active. During several tours of the USA – including the one during which this Brahms recording was made – he took inspiration from the federal structure of the host country, to develop ideas for a multi-nation Pan-Europe.

But although it’s tempting to always look forward by considering the early 1920s as the start of the modern age, it’s also good to take an occasional glance in the rear-view mirror.

Johannes Brahms died only 25 years before the date of this recording – the equivalent of a composer dying in 1997 from our viewpoint in 2022. As a young prodigy, Huberman played the Brahms concerto in the presence of the composer in Vienna (the audience also included Johann Strauss, Anton Bruckner, and Gustav Mahler!). So this performance is a link to the aesthetics and musical style of an earlier age.

This is pre-Machine Age rhythm. A human pulse, not a mass-produced beat – responding to the fluctuations of blood circulation and nerve responses of the body that occur both during dance (physical movement) and during changes of emotional state. This is music-making that exults in the joy of being free. As Huberman himself wrote,

The true artist does not create art as an end in itself; he creates art for human beings. Humanity is the goal.

[Brahms, arr Joachim: Hungarian Dance No. 1. Bronisław Huberman – violin, Paul Frenkel – piano. Recorded New York, approx. January 1922]

-

Voices of Ukraine 1922 – Part 2

It’s never possible to separate art and culture from politics. Any attempt to do so is itself a political act. The only question is whether those politics are benign and welcoming to all, or hostile and discriminatory to groups or individuals.

Cosmopolitanism versus local or national culture is a false dichotomy when it comes to art. To be a cosmopolite is to be a citizen of the world. It is not to see that world as one bland amorphous thing. Differences of regional culture and language can only enrich our understanding and appreciation of our fellow humans.

When it comes to nationalism and art we have to tread carefully. But even here, the territory can stretch between negative and positive poles, depending on context. And today’s context of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine – unusually clear in the distinction between right and wrong – allows for a wholehearted support of Ukrainian art and culture as a rallying cry in support of a desperate people.

At other times, the playing of a national anthem at concerts around the world could feel uncomfortable to a committed world citizen. But precisely now, performing the Ukrainian anthem is an act of solidarity: we are all Ukrainians now.

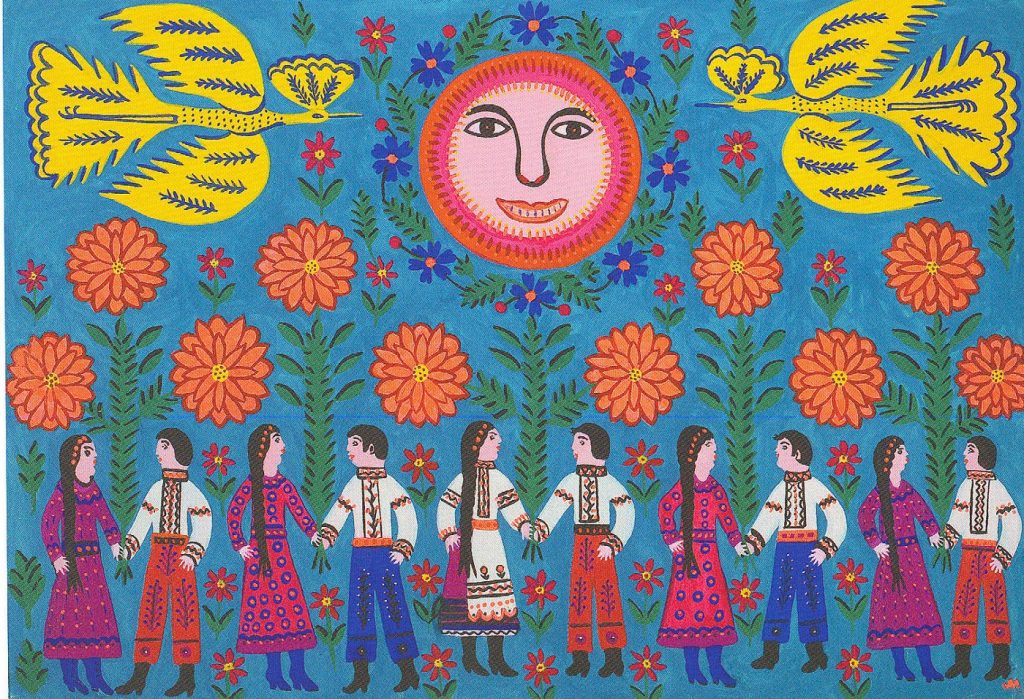

Maria Prymachenko, Our Army, Our Protectors (1978). Dozens of works by this renowned folk artist have been destroyed in a Russian attack on a museum in Ivankiv. Nina Koshetz (born Kyiv 1891) was the niece of Alexander Koshetz – the conductor of the Ukrainian National Chorus, featured in my previous post. In 1922, she was already a star of opera, both in the lands of the former Russian Empire and on tour in the USA. She broke that tour to join as soloist with her uncle’s choir and to make recordings. Most of the solo recordings were of typical – mainly Russian – operatic repertoire, but this one of a Ukrainian folk song, Winds are Blowing, has special resonance at this time of crisis.

The soprano of the former Imperial Opera of Moscow, Mme. Nina Koshetz in conjunction with the Ukrainian National Chorus (publicity photo, 1922?) Footnote: In recent years, an extraordinary project has been documenting folk songs in Ukraine. At the time of writing the Polyphony Project website has 1787 songs in high quality audio and video.

[Winds are Blowing (Ukrainian Folk Song). Nina Koshetz, soprano; Boris Lang, piano. Recorded New York, approximately October 1922]

-

Voices of Ukraine 1922 – Part 1

For a brief moment following the collapse of empires – Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman, after the First World War – an independent Ukrainian state existed: the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The Ukrainian National Chorus was formed to promote Ukrainian culture abroad and, in a triumph of what must nave been very challenging post-war logistics, it toured to 10 countries in Europe and the Americas. In the USA alone, the choir performed in 115 cities across 36 states.

Ukrainian National Chorus in traditional costume (Buenos Aries, 1923) This recording was made in New York during that tour. A very familiar tune – now known as Carol of the Bells – but here in its original form with the title Shchedryk. Nothing to do with Christmas – it comes from a tradition of songs to welcome the new year by looking for the signs of spring.

The composer of this song (or perhaps more correctly, arranger – as it’s based on a folk melody) was the choral music specialist, Mykola Leontovych. In the early hours of 23 January 1921, he was murdered by an agent of the Cheka – the brutal Soviet secret-police organisation, and predecessor of the KGB – the employer from 1975 to 1991, of Vladimir Putin, the present-day butcher of an independent Ukraine.

Footnote: A few years later, the young George Gershwin heard the choir and was particularly moved be their performance of the Ukrainian lullaby, Oi Khodyt Son Kolo Vikon. It’s possible that a memory of this tune seeped into his composition of Summertime.

[M. Leontovych: Shtchedryk. Ukrainian National Chorus conducted by Alexander Koshetz. Recorded New York, 1922]

-

First the smoulder, then the glow, then the blaze

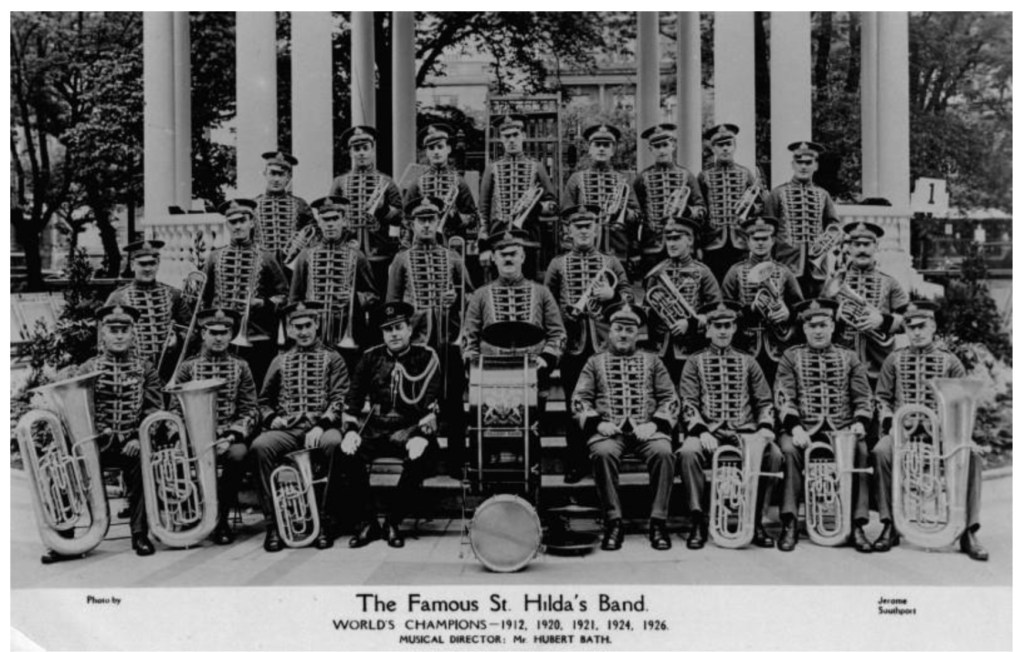

“Tone, tune, time reading, technique and expression of the finest culture.” These were the adjudicators’ comments when St Hilda’s Colliery Band won the Crystal Palace 1,000 Guinea Trophy and the Championship of the British Empire (later called simply National Championship) for the third time in 1921. The band had won in 1912, came second in 1913, and won again in 1920 (the competition was not held 1914-1919 because of the First World War). So it was a shock when the band came fourth in 1922. It seems likely that the recording session was booked on the assumption of another victory as it took place on September 25th – two days after the competition at Crystal Palace. (The score of Freedom recorded here is necessarily abridged to fit on the two sides of a 10-inch disc.)

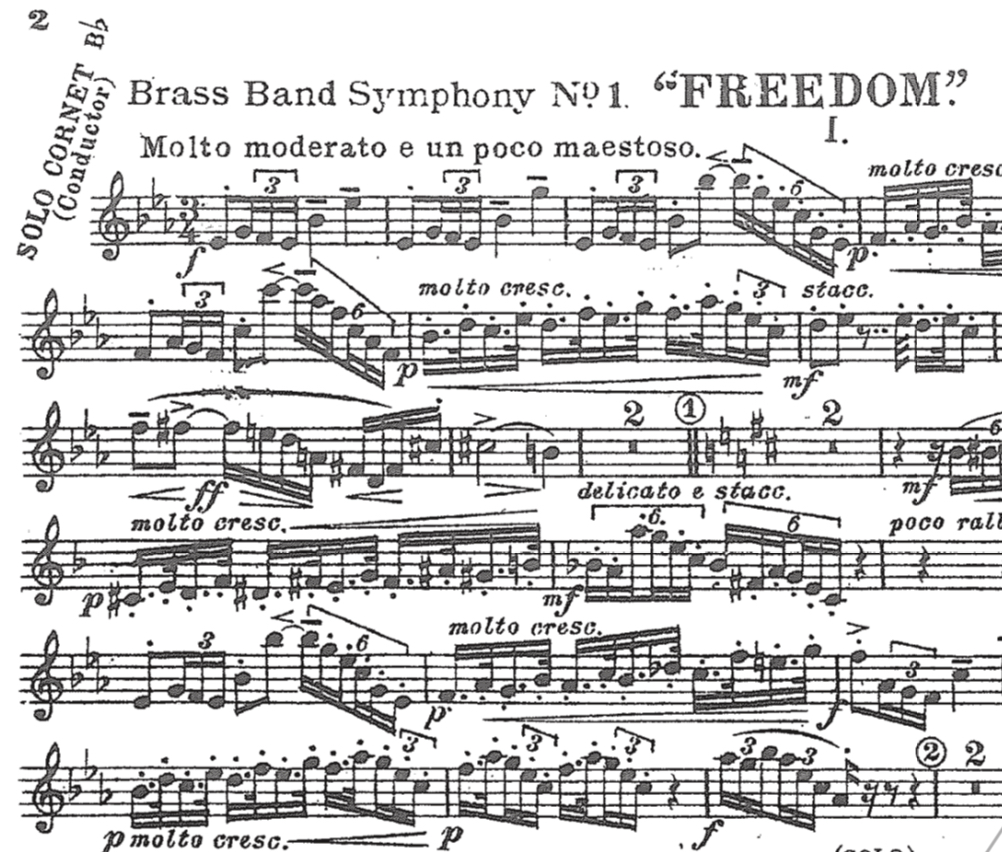

Nevertheless, it’s an impressive performance for a fourth placed band. Just listen to the virtuosity of these players – mastering music as difficult as anything in the symphonic repertoire. The opening bars bear a passing resemblance to the Finale of Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony, with the difference that the equivalent of the busy string parts are played on brass instruments with three valves, or a single slide in the case of the trombones.

A sample of the principal cornet part What makes this level of musicianship the more remarkable is the realisation that these players spent most of their waking lives working underground as coal miners in St Hilda’s Colliery, South Shields (on Tyneside, North-East England). Rehearsals were held in their limited spare time and leave was given for competitions as employers recognised the prestige that rubbed off from success (think football teams and sponsorship).

That colliery bands flourished at this time is partly due to the fact that coal miners were exempt from conscription during the war (with the exception of those Welsh miners who were sent to dig tunnels to lay explosives under German lines). Coal mining was one of the most dangerous forms of employment – 141 men lost their lives working at St Hilda’s Colliery during it’s 130 years of existence [source: Durham Mining Museum]. But men had a greater chance of survival down the pit than in the hellish trenches of the Western Front.

Part of the success of the St Hilda’s Band in these years (they want on to win the National Championship again in 1924 and 1926) was down to the work of William Halliwell who conducted them in all of their winning performances. In fact Halliwell has a still unbeaten record of conducting 17 first prizes in 26 years of the National Championships between 1910 and 1936. In 1922 alone he conducted 7 bands and they were all ranked in the top 10.

One can only imagine the feelings of the regular bandmasters who put in weeks and weeks of work training the band only for the glory to go to the star conductor who stepped in for the final few rehearsals, but he clearly was an expert in polishing a brass band. He vividly describes one such final preparation:

The band was very good by that time technically, but the general performance lacked vitality and imagination. It was my job to develop these qualities and the progress during that day might be described as something like lighting a fire. First the smoulder, then the glow, then the blaze.

From a speech to the Rotary Club of Wigan, 1925Hubert Bath’s Freedom (Brass Band Symphony No.1) was representative of a new style of competition test piece. Before the war, the set work usually consisted of an arrangement of a well-known orchestral piece, such as the William Tell Overture. But as standards of playing got higher and higher, contemporary composers were commissioned to write new, ever more challenging pieces, a tradition that continues to this day. (For a more recent example of mind-blowing virtuosity, have a listen to Philip Wilby’s Masquerade.)

The extra-musical subject matter of these pieces often combined a non-conformist religious sensibility with a sort of patriotic escapism. It’s almost as if the revelatory visions of William Blake have been reborn a century later in the new brass band repertoire. The composer’s notes in this score describe an idyll that must have been out of the reach of most Tyneside miners:

First Movement: In God’s fresh air, under the open sky, we stretch our arms to the great spaces, breathing the winds and contemplating the gentle sweetness of Nature itself. This is Freedom.

Second Movement: And then, the quiet interlude of Romance, the trees, the meadows, the scent of the flowers, the little drifting clouds, and — Love. This, too, is Freedom.

Third Movement: And then, again, that other insuperable gift of Laughter, fresh and light as the salt sea breezes over the hilltops which have fluttered their songs across the laughing waves. This is Joy, Love, Vigour, and— This, also, is Freedom.

Within a decade, the pastoral idyll had completed its move to the countryside, well away from the grime of heavy industry – most prominently in the “trilogy” of Holst’s A Moorland Suite (1928), Elgar’s The Severn Suite (1930), and Ireland’s A Downland Suite (1932), works that are just as poignant today with our awareness of manmade environmental degradation, not least that caused by the burning of coal and other fossil fuels.

But the modern style of test piece was not universally popular. In a review of the 1922 Championship, composer and conductor James Ord Hume wrote:

From a personal point of view, and from many years’ experience, both as a judge and writer of brass band music, I cannot agree that brass bandsmen are in favour of the test piece of the last decade. The fact remains that they have never become popular as test pieces, and they never will become popular, either with contest committees or with bands or audiences… Brass bands are a popular institution, and they are undoubtedly the ”people’s orchestra”, and the people enjoy popular brass band music just the same as another class of the musical public enjoy their orchestra or oratorio. It is the brass band that brings the opera, musical play, oratorio, and other musical arrangements to the humble worker, who otherwise would never hear such music; and they prefer this to music that can only be played or heard by some twenty bands out of a total of over 30,000 bands in Great Britain alone.

Musical News and Herald, September 30, 1922So let’s whet the appetite of the humble worker with popular pieces but save the challenging stuff for “another class of the musical public”. Try telling that to the countless players who have populated the brass sections of British orchestras over the past century, many of whom came through the brass band movement. And how many aspiring young musicians have had their musical horizons widened by local bands when official teaching provision has failed or simply not existed?

As for the St Hilda’s band, they managed to survive when the pit was closed down in 1925 by touring and earning income from performing concerts, but the downside of this was that they were deemed to be a professional band and so were disqualified from competing in the National Championships after their fifth and final victory in 1926. They managed to keep going for another decade until the realities of running a full-time brass band during an economic depression caught up with. them. Their eventual demise was marked with this unassuming advert in the Musical Progress and Mail of December 1937:

[Hubert Bath: Freedom (Brass Band Symphony No. 1), St Hilda Colliery Band. Recorded September 25, 1922]

-

Will the real Mr Rachmaninoff please stand up?

A masterly transcription of an orchestral piece by Bizet. With minimal changes to the original (written 50 years before these recordings, in 1872) – just a few chromaticisms in the figurations and an occasional spicy chord – it has been transformed into a Rachmaninoff-sounding piano miniature. It’s as though Rachmaninoff recognised his doppelgänger in the earlier composer:

If you are a composer you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my pianoforte interpretations, color. So you can make music live. Without color it is dead.

From an interview with Rachmaninoff, Musical Opinion, 1936I’ll come back to the concept of musical colour later.

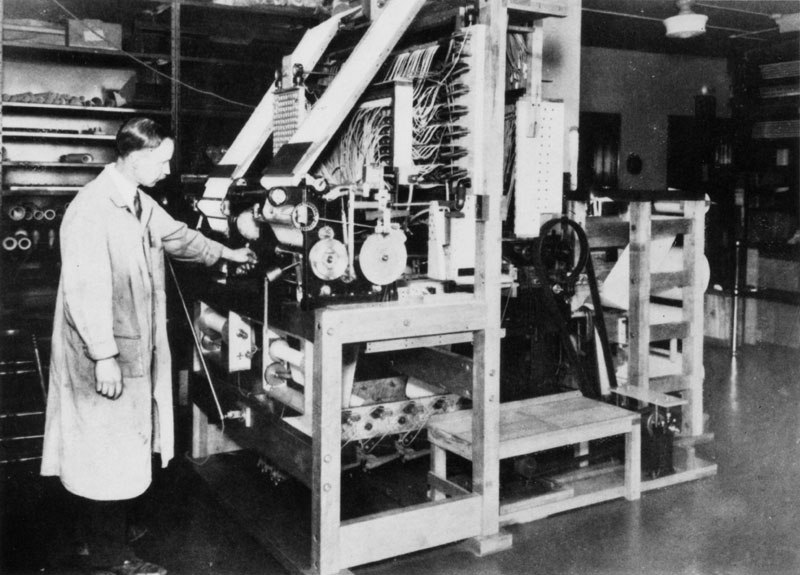

Two recordings of the same piece made 40 days apart in early 1922, using the most advanced technologies of the time.

The first, an acoustic recording of Rachmaninoff playing a Steinway model D in the Victor recording studio in Camden, New Jersey: two large recording horns (one for the treble, one for the bass strings), whose diaphragms sent vibrations to a stylus engraving a groove into a soft wax master disc.

The second, a modern recording of a restored Ampico reproducing player-piano, playing a piano roll containing an “imprint” of Rachmaninoff’s performance on a Mason & Hamlin piano in Ampico’s New York studio.

Both of these technologies were to be superseded in the following few years: acoustic recording by electric recording using microphones and amplifiers in 1925, giving a greater dynamic and frequency range; Ampico’s reproducing piano by its model B system in the same year, allowing more subtleties of the original recording to be imprinted and reproduced.

So which of the two recordings is closer to hearing Rachmaninoff playing the piano? On first impressions, the piano roll is the more impressive. We are hearing a modern recording – we can hear more detail of sound and even see the ghostly movements of the piano keys. And other piano rolls have even been subject to modern computer technology, going so far as to produce a virtual reproduction of Rachmaninoff’s hands.

The headline in the above link rings some very high-frequency alarm bells for me: “This AI has reconstructed actual Rachmaninov playing his own piano piece” it states confidently. That “actual” is doing a lot of work in the headline and brings me to the “actual vs virtual” dilemma.

What “actually” went on in the process of producing a piano roll? I’m not going to get into the specifics of the electronics and hydraulics involved. It’s enough for my purpose to know that at this time, rolls could record and reproduce only notes, rhythm, and articulation. In other words, they couldn’t deal with musical colour – the “most important thing” for Rachmaninoff as a performer. For the subtleties of dynamics involved in touch and tone, an army of technicians was employed to make thousands of adjustments to the roll in an attempt to replicate the playing of the original performer, overseen by the musician’s personal editor: in Rachmaninoff’s case, Edgar Fairchild – an accomplished pianist in his own right.

Ampico Master Perforator – New York, 1927 So not so different from a modern recording process’s editorial box of tricks for correcting or ’improving” an original take.

Now let’s take a slight detour to the aesthetics of listening to live (and “in-person”) versus recorded forms of music. The medium that often blurred this distinction was radio, which was just starting to get going in 1922 (the year the BBC was founded). Interestingly, Rachmaninoff refused to make radio broadcasts, which are yet another form of “at home” listening, involving mainly unedited broadcasts of live concerts. His views are worth quoting in full as his reasons are not to do with the technical quality of sound, but raise deeper issues.

Radio is not perfect enough to do justice to good music. That is why I have steadily refused to play for it. But my chief objection is on other grounds. It makes listening to music too comfortable. You often hear people say “Why should I pay for an uncomfortable seat at a concert when I can stay at home and smoke my pipe and put my feet up and be perfectly comfortable?” I believe one shouldn’t be too comfortable when listening to really great music. To appreciate good music, one must be mentally alert and emotionally receptive. You can’t be that when you are sitting at home with your feet on a chair. No, listening to music is more strenuous than that. Music is like poetry; it is a passion and a problem. You can’t enjoy and understand it merely by sitting still and letting it soak into your ears.

Interview with Rachmaninoff for Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Paris 1927Of course, the argument could apply equally to records, listened to at home with your feet on a chair (the cynic in me suggests that maybe the fees for radio broadcasts were not as generous as his deals with RCA Victor), not to mention listening to music on your iPhone whilst scrolling through your Facebook feed, but the phrase that I love – and that might just become a personal motto – is that music is “a passion and a problem”. Rachmaninoff was not just the “heart on his sleeve” romantic of conservative repute, but a musician – both as composer and performer – of both heart and head (he was often regarded as quite a cerebral performer by his contemporaries). His objection to some forms of musical modernism was that they often prioritised head over heart. But what is clear from the words above is that Rachmaninoff wanted the listener to take an active part in the musical process – to be a problem solver as well as a fully rounded receptive human being.

So maybe the argument over which recording represents the “real” Rachmaninoff is less important than the more exciting realisation that we – as listeners – can become virtual editors or virtual “master perforators” of the music that we hear, whatever the technical medium that presents it.

[Bizet, arr. Rachmaninoff: Menuet from L’Arlesienne Suite No. 1. Recorded Camden, New Jersey, 24 February 1922]

[Bizet, arr. Rachmaninoff: Menuet from L’Arlesienne Suite No. 1. Recorded on Ampico piano roll 6 April 1922]

-

“At night when you’re asleep, into your tent I’ll creep,” sang The Beatles

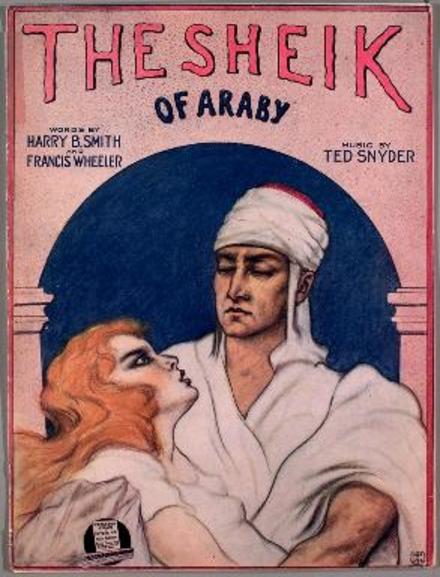

A Jewish Russian-Hungarian band leader (Dajos Béla) and his Berlin-based salon orchestra (Künstler-Kapelle) playing an Arabian shimmy (“Arabischer Shimmy”) by an American composer (Ted Snyder) written in response to a book by an English author (Edith Maud Hull), and made popular by a hit silent film (The Sheik), starring an Italian actor (Rudolph Valentino). What is going on?

This is the story of a hit tune, a blockbuster film, and a bestselling novel. And all throw a spotlight on the sexual politics and colonial attitudes prevalent in American and European popular culture in 1922.

First, the tune.

A quick bit of musical analysis: the tune uses the so-called “Arabic scale” or “double harmonic major scale” (containing two major seconds: F, Gb [only in the harmony here], A, Bb, C, Db, E) – often used by composers to evoke an all-purpose oriental character, as in the Bacchanale from Saint-Saëns’s opera Samson and Delilah (1877). Throw in some cymbal crashes, a sprinkling of castanets (actually they sound like wood blocks here – they’re louder, I guess) and season with a dash of wailing oboe, and we’re almost there. All that’s needed is a cheeky quote from Grieg’s Peer Gynt (at 1’33’’), whose eponymous hero also ends up in the North African desert, and we’re done.

Ted Snyder’s Tin Pan Alley tune – titled fully as The Sheik of Araby – was soon taken up by musicians and recording companies far and wide. There are several other versions from 1922, including a very similar arrangement by Eleuterio Yribarren and his Red Hot Pan American Jazz Band recorded in Buenos Aries.

The tune quickly became what was then a new phenomenon – a jazz standard. There are countless recorded versions from the following decades that together make a mini history of jazz styles. As most versions concentrate on the second half of the tune, there is not much left of the oriental flavouring. Here is my personal selection:

- 1922 – A virtuosic ragtime version for piano roll by Zez Confrey

- 1932 – Duke Ellington – including a rare soprano sax solo (1’29″) from Johnny Hodges, the regular alto player (apparently he visited Sidney Bechet’s apartment the night before the recording for a lesson).

- 1937 – Stephane Grapelli and Django Reinhardt doing their Hot Club du France thing.

- 1937 – possibly my favourite version: Art Tatum at his most inventive, using the whole range of the piano in this miniature masterpiece – the musical equivalent of drinking the perfect espresso. His rare inclusion of the first part of the tune allows for about 15 seconds of almost Debussyian harmony (from 0’28″), which also highlights the tune’s similarity to Gershwin’s It Ain’t Necessarily So of two years earlier.

- 1939 – Jack Teagarden sings and plays on the B side to another orientalist tune, Persian Rug.

- 1941 – An early experiment in multi-tracking: Sidney Bechet playing clarinet, soprano sax, tenor sax, piano, bass, and drums.

- 1942 – a Nazi propaganda version by Charlie and His Orchestra. Although jazz was officially banned by the Nazis, this German swing band was formed to broadcast on international shortwave radio. As with their other productions, it starts with the original lyrics, then is hijacked by anti-British propaganda..

- 1945 – The 19-year old Oscar Peterson in his first recording session: boogie-woogie with a hint of early rock and roll.

- 1962 – And that mention of rock and roll leads nicely to the most unlikely version of all. Forty years after the song’s first recording, The Beatles (with George Harrison on vocals and Pete Best on drums) recorded The Sheik of Araby as part of their unsuccessful demo session for Decca, whose executives judged that “the Beatles have no future in show business”.

What about the book that spawned the song and then the film? Marketed in a recent rewrite (or rip-off?) as ”Pride and Prejudice in the Desert”, E.M Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik (which sold in the millions soon after publication) follows the Jane Austen plot-line of an independently-minded woman and an overbearing man, who come to love each other in the end. But the narrative – set in French colonial Algeria – is overlaid with the culture clash of European woman meets Arabian man, made horrifyingly morally dubious – to say the least – by the man raping the women after she is captured (between chapters in the book, between scenes in the film) and finally falling in love with her. The dénouement comes when he reveals that he is not an Arab after all. His father was English, his mother Spanish, so all is well!

The two live happily ever after in the desert, leaving the reader with the final specter of an aristocratic English couple “gone native,” it is true, but reigning imperialistically over the unruly Bedouin tribes of the Sahara in an area which was nominally under French colonial control.

Hsu-Ming Teo, 2010For any interested readers, there are many online articles of literary criticism about the novel, but a good summary of the issues of sexual, racial, and colonial politics (and how the differing post-First World War experiences of the UK and USA are reflected in the English novel and the American film) can be found in the article quoted above.

The film and its sequels made Valentino a star. And the fashion in Europe for all things oriental (however vague and stereotyped that fashion) increased exponentially from this time on, and was given a huge boost by the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt in November 1922.

The cartoon version of sheiks and Arabia has never really disappeared – there’s even a Muppet rendition of the song – and newly written “desert romance” novels increased in popularity in the early 2000s.

What’s missing, of course, is any voice from the Arab world itself. In 1922 much of that world was ruled under the Mandate system, established after the First World War by the League of Nations (principally Britain and France) because – according to Article 22 – the local peoples were not considered “able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world”. The areas’ governance was to be “entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake this responsibility”.

And a final footnote to show just how far the meme of the desirable sheik has spread. In Faroese – the language of the Faroe Islands where I live – the common slang word for boyfriend is “sjeikur” (i.e. sheik).

[The Sheik – Arabischer Shimmy (Ted Snyder), Künstler-Kapelle, Dajos Béla. Released 1922]

-

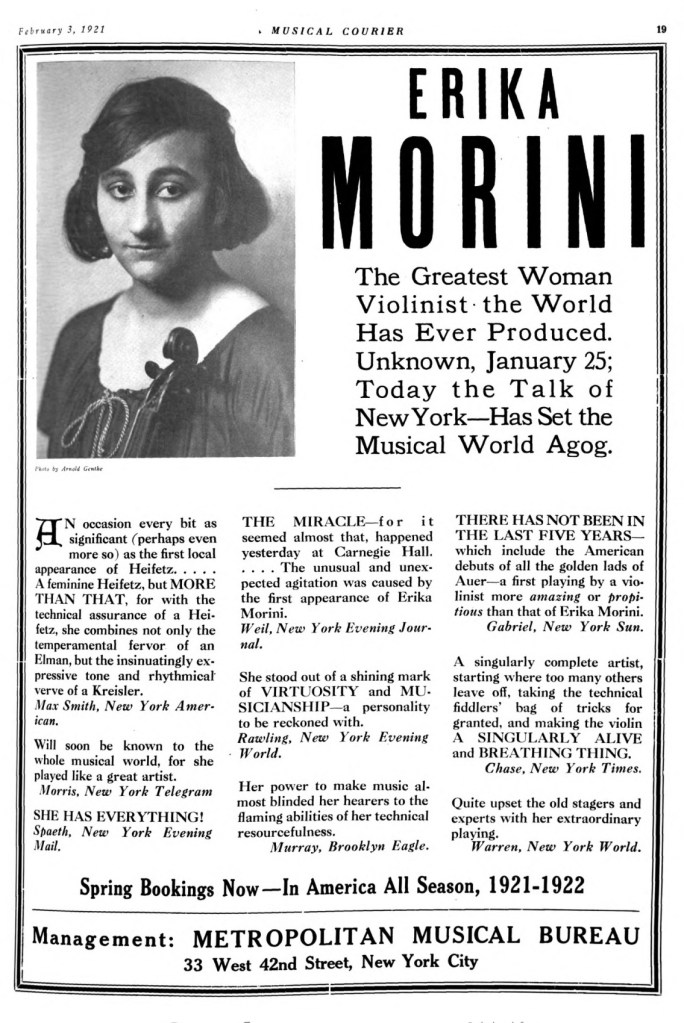

“The Greatest Woman Violinist the World Has Ever Produced. Unknown.”

Two sisters from Vienna. Erika, about 17 years old, sits casually – her right leg underneath her, holding a copy of the Musical Courier. She wears a sailor-suit ribbon to emphasise her youth. Her smile still has a hint of adolescent self-consciousness about it. Alice, 8 years older, sits on the arm of the sofa and stares at the camera with a more knowing look. A publicity shot for their first American tour, though neither sister is new to being in the public eye. After all, Erika had played at a birthday party for Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph at the age of 5 and had already played concertos with Fürtwängler in Berlin and Nikisch in Leipzig while in her early teens.

This photo was probably taken shortly after Morini’s Carnegie Hall debut on January 16, 1921 in New York. The concert was a sensation and was followed by a 60-date tour of North and South America over the next few months. Soon snapped up by the Victor Talking Machine Company, in March and April 1921 the two sisters were taken to the studio in Camden, New Jersey where they recorded a few short pieces, including Wieniawski’s Cappriccio-Valse. They played it 7 times. Take number 5 was selected (the other 6 were destroyed) and it was released on several labels in 1921 and 1922.

It’s a typical violin showpiece, but played with such wit and sophistication that it doesn’t sound like showing off. It’s like watching a masterful trapeze artist: the thrill of seeing almost-impossible patterns drawn in the air, alongside a slight buzz of danger, balanced by the conviction that the artist is in complete control. The recording is pre-electrical: microphones didn’t come in until 1925. The large horn used to capture sound had a limited dynamic and frequency range, so how is it possible that we can still appreciate Morini’s superlative violin tone? Does our brain compensate for the lack of high fidelity, in a similar way that we don’t necessarily miss the lack of colour in black and white photographs?

The copy of the Musical Courier (“Weekly Review of the World’s Music”) in Erika’s hands could be the one containing the advertorial from her tour management reproduced below. A search of the magazine’s archive online in the period of the American tour reveals a strikingly modern approach to PR and its attendant hype. There’s the fake news of reports from the Viennese press that Morini was getting paid $6,000 per concert; the cringeworthy interview asking about boyfriends.

And what about the next 50 years of Erika Morini’s career? (She gave her last concert in 1976 and died in 1995, having, in 1938 – as a prominent Jewish musician – made the inevitable move to the USA.) She certainly continued to play at the highest level, and there are some wonderful recorded performances, including a riveting Tchaikovsky concerto from 1940 with Stravinsky conducting the New York Philharmonic. But she never received the attention of her male peers. Even today, Heifetz has about 340 times as many monthly listeners on Spotify, and Kreisler about 1300 times.

So it somehow seems even more poignant to listen to these glittering four and a half minutes of recorded time from one hundred years ago and imagine what might have been.

[H. Wieniawski: Capriccio Valse, Op. 7. Erika Morini – violin, Alice Morini – piano. Recorded Camden, New Jersey April 6, 1921. Released 1922.]

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.