It must have been a Thursday in 1977 or 78. After school, my father drove me to my clarinet lesson with my new teacher – John Melvin, who was Head of Music at Oxford High School. He was a warm and encouraging mentor and taught music as an expressive language, not overly concerned with the finer points of clarinet technique. (He was also the inspirational conductor of the local youth orchestra – which I joined soon after: coaxing, rather than commanding, the best from his young players.)

His teaching room was a mess, the grand piano hardly visible under piles of scores, books, and records. He hardly ever demonstrated on the clarinet (he didn’t play much in those days), but he passed on lots of knowledge and insights from his teacher, Frederick Thurston (1901-1953, founding principal clarinettist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra), and other musicians of an earlier generation.

At this particular lesson, I think we must have been working on one of the Brahms sonatas, and he started enthusing about the legendary English clarinettist, Reginald Kell – still then regarded as something of an eccentric for his use of continuous vibrato. As I left the lesson, in one hand I held my clarinet case and music, and under the other arm I held a brown square box, carefully trying not to drop it before I reached the car. The box contained four original shellac 78rpm discs of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet, performed by Kell and the Busch Quartet.

Remarkably, our stereo gramophone could still play 78s (in fact, I’m pretty sure that, as well as 78, 45, and 33 & 1/3 speeds, there was even a 16 rpm setting!).

At home we had an LP of the Kell recording with the Fine Arts Quartet, recorded in the US in 1951. But this 1937 London recording with the Busch quartet was something else: sinewy, expressively free, but also rhythmically taut, and imbued with a sort of sweet pain – almost unbearably heart-wrenching, yet ultimately consoling.

This was my first exposure to the sound world of the Busch Quartet. Beyond the scratches and fizz of the old recording, I marvelled at this tradition of mittel-European music-making, seemingly still rooted in the rich soil of nineteenth-century chamber music performance practice, but with a steely, modern fidelity to the score – the perfect combination of heart and intellect.

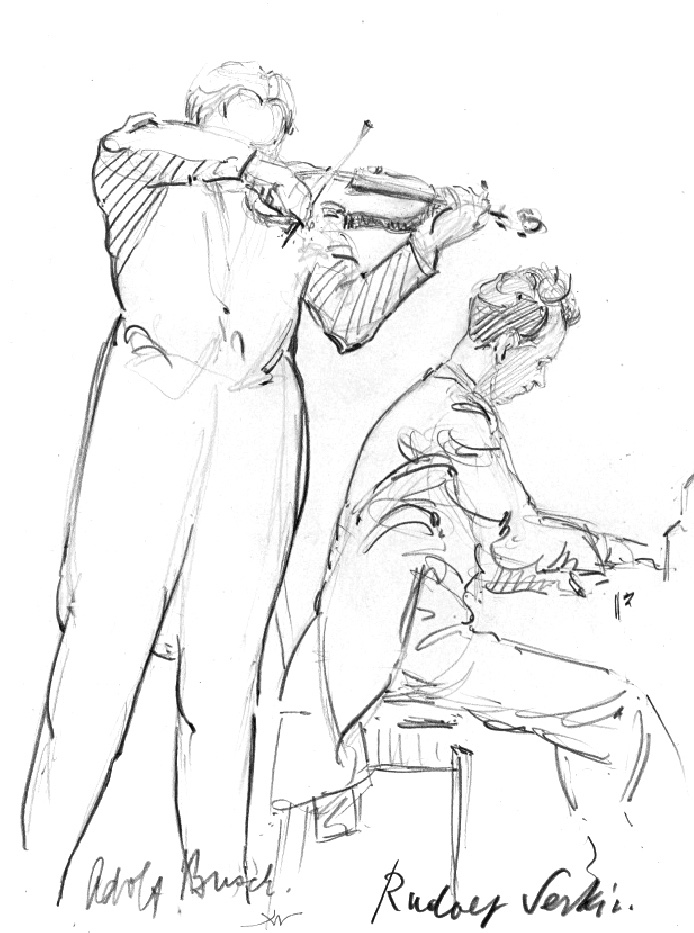

Later on, I discovered more Busch Quartet recordings, reissued on LP and then CD: the Beethoven late quartets, of course; Schubert chamber music, and duo recordings of Adolf Busch – the first violinist – with the pianist Rudolf Serkin. And it’s to one of the great collaborations of Serkin with the full quartet that I want to turn now: the EMI recording of Brahms’s Piano Quintet in F minor, op.34, made at Abbey Road Studios, London on 13 October 1938.

Five years before this recording was made it was the centenary of Brahms’s birth. The year 1933 was significant for more sinister reasons, of course, as this brief news report in Time magazine from 1 May 1933 makes clear:

In Manhattan last week arrived bristly haired, professional Violinist Adolf Busch bringing to the U. S. for the first time his famed Busch Quartet and his young protege Pianist Rudolf Serkin. Day before they landed came news that Busch, like many another German musician, had found Adolf Hitler’s government more than he could stomach. Busch had been engaged for Brahms centennial concerts in Hamburg this month, but Pianist Serkin, a Jew, was not to be allowed to play. Violinist Busch withdrew.

Adolf Busch never played in his homeland again. He was already living in Switzerland and attempts to lure him back to Germany were answered with somewhat stringent conditions: “If you hang Hitler in the middle, with Goering on the left and Goebbels on the right, I’ll return to Germany.” He wasn’t one for sitting on the fence!

By 1938, the only two European countries where Busch and Serkin would play were Switzerland and Britain.

The Busch-Serkin relationship was one of the great musical partnerships, and their chamber music groupings were literally family affairs: Adolf Busch became Serkin’s father-in-law when Rudolf married Adolf’s daughter Irene in 1935, and Adolf’s brother Hermann played cello in the quartet. And they worked so intensely together that they often performed concerts from memory (including complete cycles of the Beethoven violin sonatas).

Let’s now consider the date of this Brahms recording: 13 October 1938: less than a month before Kristallnacht (9-10 November), and just a few days after German forces started to occupy the Sudetenland, including the town of Eger (Cheb in Czech) – Rudolf Serkin’s birthplace. And seven months earlier (12 March) German troops had entered Austria, trapping Serkin’s mother and his siblings in Vienna.

In London on 30 September, Neville Chamberlain stood outside 10 Downing Street, having returned from Munich, believing he had given Hitler everything he wanted, to prevent war: “My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time. We thank you from the bottom of our hearts. Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.”

Winston Churchill thought otherwise, of course, and on 16 October he gave a radio broadcast to the United States from London, in which he said:

The stations of uncensored expression are closing down; the lights are going out; … The light of civilised progress with its tolerances and co-operation, with its dignities and joys, has often in the past been blotted out. But I hold the belief that we have now at last got far enough ahead of barbarism to control it, and to avert it, if only we realise what is afoot and make up our minds in time.

What has all this got to do with a piece of chamber music by Brahms, written 70 years earlier, and recorded on an autumn day in a studio in St. John’s Wood, north London? My answer is: nothing and everything.

Leave a comment