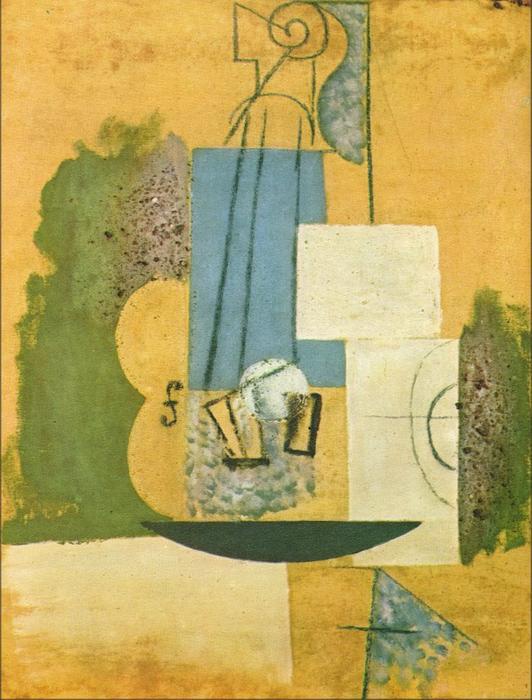

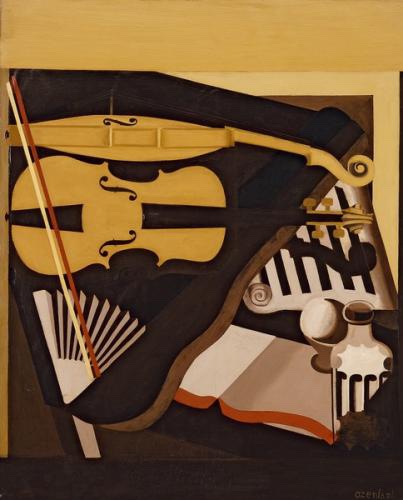

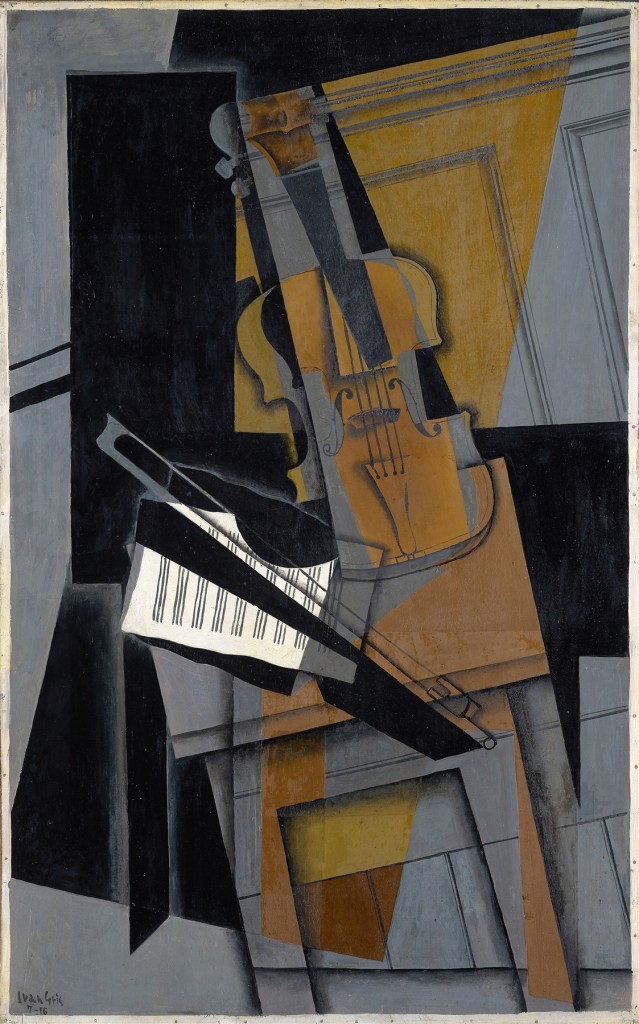

In the early years of the twentieth century, the violin achieved iconic status in European culture in an almost literal sense. Whereas Renaissance painters looked to the Madonna and Child as worthy subjects for art, modernist artists – putting their faith in more secular imagery – often turned to the violin to represent one of the peaks of human achievement for a new post-religious age.

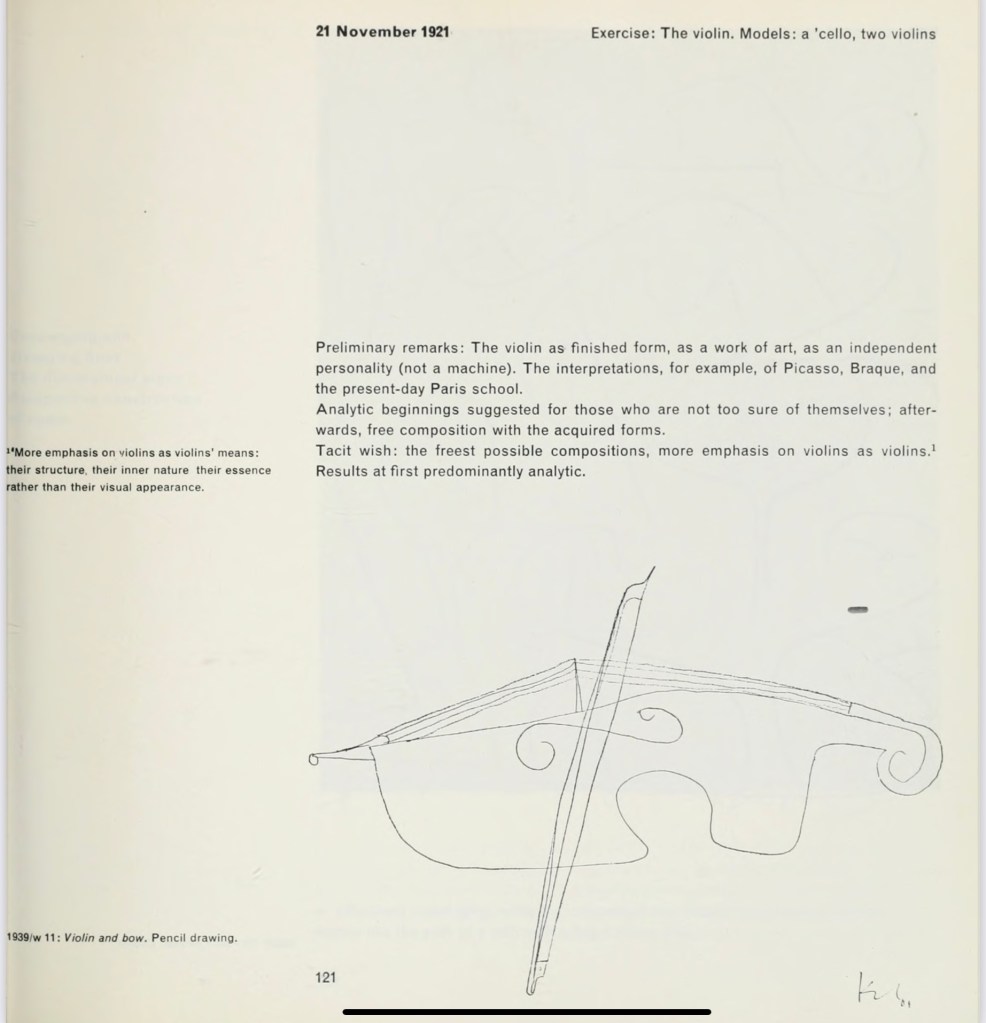

In his notes for a lecture at the Bauhaus, Weimar in November 1921, the Swiss artist Paul Klee asks his students to treat the violin “as an independent personality (not a machine)”. This is the violin representing human individuality in opposition to the anonymity of the machine age.

The violin – both as a perfectly crafted musical instrument and as a vehicle for supreme human artistry – combined urban high art and rural folk culture: the salon as well as the tavern. It is no accident that the violin plays a key rôle in Stravinsky’s tale of the everyman-soldier, L’Histoire du Soldat (1918).

It also took centre stage in the early days of the International Society for Contemporary Music. At the first unofficial festival in 1922 preceding the ISCM’s formal founding, and the first official festival in 1923 (both in Salzburg), several recent works for violin were chosen for performance, including no fewer than six masterly violin sonatas: by Carl Nielsen (written in 1912), Leoš Janáček (1914-15, revised 1916-22), Florent Schmitt (1919), Ernest Bloch (1920), and two by Béla Bartók (1921 & 1922).

These six violin sonatas are all substantial works and, together, they illustrate the wide variety of contemporary music on offer at these early ISCM festivals, from composers outside the dominant Austro-German mainstream (from Denmark, Czechoslovakia, France, Switzerland/USA, and Hungary). Yet, despite the diversity of styles and compositional approaches, the six works have much in common. They are all serious attempts to take a traditional form in new directions and to challenge the virtuosity of performers on both violin and piano. And each sonata is drenched in human passion and intellectual inquiry, together forming a boxed set of exploratory musical narratives for a new age.

I have made a Spotify playlist of the six sonatas. I recommend listening attentively to this music. This is not music for the car stereo or for accompanying social media scrolling! What follows are “listening notes” in the sense of “tasting notes” in descriptions of fine wines, based on close listening, so don’t expect detailed analysis of the music or extensive biographical information.

Composed between his third and fourth symphonies, Carl Nielsen’s Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 35 is neither expansive nor inextinguishable, with its compact and concise opening movement and a short finale that peters out like a fluttering match. The weight of the central Molto adagio, however, anchors these two flighty outer movements to solid ground.

The wandering violin theme that opens the sonata has a pre-echo of Shostakovich about it in its reticent searching. Nielsen has a liking for unusual tempo qualifiers, and this one – Allegro tiepidézzo (tepid or lukewarm) is particularly intriguing. Is it a reluctance to get involved? (The beginning is also marked senza espressione.) The rapid shifts of tonality certainly suggest a reluctance to settle down.

The stabs of pain at the start of the Molto adagio ripple throughout the rest of the movement. But this is an adagio that also contains the comfort to salve these wounds.

The finale has the spirit of a gentle scherzo, making its abrupt quiet ending seem even more premature: are we not expecting another movement to follow? The marking Allegro Piacevole (agreeable, pleasant) is also used by Beethoven as the triple-time finale to his 2nd Violin Sonata, a work that Nielsen the professional violinist was surely acquainted with. Nielsen’s Allegro – although benignly agreeable – has a slight feeling of discomfort due to the fact the the stress is mostly on the “wrong beat”: the upbeat that it starts with is felt as a downbeat, and this rather cheeky deception continues for much of the movement.

All the composers featured here were in their 40s when they wrote their sonatas, except Leoš Janáček, who was 60 years young when he started his Violin Sonata, with most of his mature operas still ahead of him. This sonata is like a micro-opera in 4 acts, lasting a total of 17 minutes – a psychological drama, compelling in its compressed intensity: listening on headphones is an almost claustrophobic experience. Janáček achieves this with his technique of repeating short obsessive motifs: crystallising in three or four notes, what might take other composers a whole melodic paragraph or harmonic progression to express. And by doing this he captures states of mind and fleeting nervous emotions that more long-winded composers often miss. Whether or not this sonata was written in response to events of the First World War as some sources suggest, this music is raw, and contemporary in a genuine sense: emotions experienced in real time, not remembered with nostalgia.

out of the past, or as you walked by the open window

a violin inside surrendered itself

to pure passion.” (from the First Duino Elegy by R.M. Rilke, published 1922, trans. Mark Wunderlich)

While some composers scaled back their musical style in response to the straitened times immediately following the First World War when large orchestral commissions were harder to come by, others turned their chamber compositions into quasi-orchestral works instead. In Florent Schmitt’s Sonate Libre the phenomenally difficult piano part – often written across three staves – provides a pretty convincing substitute for a full symphony orchestra, with a kaleidoscopic pallete of tone colour.

The full title of this startlingly seductive work is Sonate libre en deux parties enchaïnées (ad modum clementis aquæ), or “Free sonata in two linked parts (in the manner of gentle water)”. This subtitle invites associations of water-related adjectives to describe this music: fluid, liquid, meandering, flowing. And this is key to understanding and following what otherwise might seem a superficially amorphous piece. As Heraclitus famously wrote of not being able to step into the same river twice, this music is constantly changing – even when a phrase recurs it is never heard in exactly the same way. Schmitt clearly learnt this technique of perpetual variation (as much else of his musical language) from Debussy, whose late orchestral work Jeux (1912) exemplifies this approach.

And some of the ravishing additive harmony is aurally dazzling: listen to the chord that ends the first movement, which contains no fewer than nine different notes; or the effervescent Messiaen-like fizz of the sonata’s sparkling coda.

The Violin Sonata No. 1 by Ernest Bloch is the big discovery for me. From the very start this music grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go. It’s earthy and rough, but also passionate and sensual. The first movement kidnaps the listener and you have no choice but to be taken along for the ride. It also has a freshness of utterance with its use of distinctive modal scales, that persuade and cajole with insistent repeated motifs and hurtling rhythms.

The slow middle movement is a ghostly shadow of the first movement, as though the obsessions of the first movement continue to disturb, even when the mind and body are trying to rest.

In the finale, daylight starts to shine on the recurrent motifs and harmonies, and the final resolution on an E major chord is like weak sunshine finally appearing through the mist.

What’s remarkable about this music is how unified it is in style, with a harmonic language quite distinct from other contemporary tonal languages. There are echoes of Stravinsky, Debussy and others, but Bloch’s voice is unique and revelatory.

We have a huge advantage over the original audiences at the early ISCM festivals: we can listen to these pieces again and again. This is particularly pertinent to the two violin sonatas by Béla Bartók – complex pieces that reveal more of themselves on each hearing. Hungarian as a language is famous for being unlike most other European languages, and Bartok’s music is likewise one of a kind, revealing complex aspects of thought and emotion that elude more mainstream composers.

Bartók’s Violin Sonata No. 1 bears the imprint of the soundworld of the big radical stage works of the composer’s early maturity: the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, and the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin. But as with the Janáček sonata discussed earlier, the drama is distilled down into chamber music size that, nevertheless, goes far beyond the domestic boundaries of traditional chamber music. And the first movement, in particular, stretches the bounds of tonality too, with its ever-widening intervals in the violin line and dense chords, whether arpeggiated or not, in the piano part.

The unaccompanied violin melody that opens the Adagio second movement is almost 12-tone-row-like in its avoidance of a tonic root. When the piano enters with the first pure triadic chords of the whole sonata, it is like balm for the soul, and here we enter the dreamworld of Bluebeard’s castle grounds.

For the finale, we are hurled into a manic folk dance, occasionally stopping for breath, before launching into ever wilder dashes for the finish.

Bartók’s Violin Sonata No. 2 can be heard almost as a continuation of the first sonata (the two works follow each other in the composer’s catalogue of works), but there is an inward turn in the atmosphere of the first movement. The ideas are fragmentary, exploratory (a musical equivalent of the cubist paintings shown here), and even perhaps a bit hallucinatory – like thoughts one might have when unable to get to sleep. Only the recurring tender brief melody, first heard in the opening bars, gives some solace: the gentle rocking of a line from a lullaby.

The second movement – which follows without a break – makes sense to me if I hear it as a response to the age of machines and production lines. Yes, it stems from folk dance again, but this time there is something almost non-human about it. The Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R., which introduced the word robot to the world was premiered in 1921 (and already translated into 30 languages by 1923), and Bartók was not immune from being affected by the zeitgeist. Only at the very end is the lullaby phrase alluded to, and the piece ends – astonishingly – on a quiet, simple C major triad, the three notes spread over a range of five octaves.

How to sum up up these six masterpieces, all performed in the first two years of the ISCM (1922 and 1923)? If they can be said to be “about” anything, let’s just say they are explorations of the autonomous individual as viewed from the inside. Intimate, heart-wrenching, honest testaments from a time when everything was being questioned, nothing was certain. Six wagers on the human (non-religious) soul, whatever that is, played on one of the most perfect of objects ever created by human hands: the violin.

Leave a comment