British classical music in the early twentieth century was dominated by the teaching of an Irishman: Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 – 1924), Professor of Composition at the Royal College of Music since its founding in 1883, and Professor of Music at Cambridge University since 1887, where he established Music as an academic subject requiring a three-year degree.

Draw up a list, haphazard, of the most prominent British composers of recent years, in every branch of writing, and you will find that it consists principally of Stanford’s pupils. Let me enumerate just a few of of the best-known names: Charles Wood, Hamish MacCunn, Walford Davies, Coleridge Taylor, William Hurlstone, Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, John Ireland, Frank Bridge, Rutland Boughton, Cyril Rootham, Nicholas Gatty, Martin Shaw, Edgar Bainton, James Friskin, Herbert Howells, Ivor Gurney, George Butterworth, Rebecca Clark, Arthur Benjamin, Arthur Bliss, Eugéne Goosens.

Thomas Dunhill: Proceedings of the Musical Association, 1926-1927

Just two of these names concern us here: Frank Bridge and Ivor Gurney. Stanford – as composer and teacher – was a bulwark of Victorian conservatism (Debussy, Richard Strauss, and even Delius were regarded as dangerous radicals by the professor), and his predominance in musical life for so long is part of the reason that British music largely bypassed European modernism. But that’s not the whole story. The First World War shook things up in Britain, just as much – if in quieter ways – as in the more revolutionary parts of continental Europe.

Even these two light string quartet miniatures by Frank Bridge – arrangements of two popular English songs – show both sides of the musical reaction to the Great War: an aching nostalgia for a pre-war idyll combined with hints of a more experimental and disorienting use of harmony of the kind that might have made Sir Charles a bit twitchy.

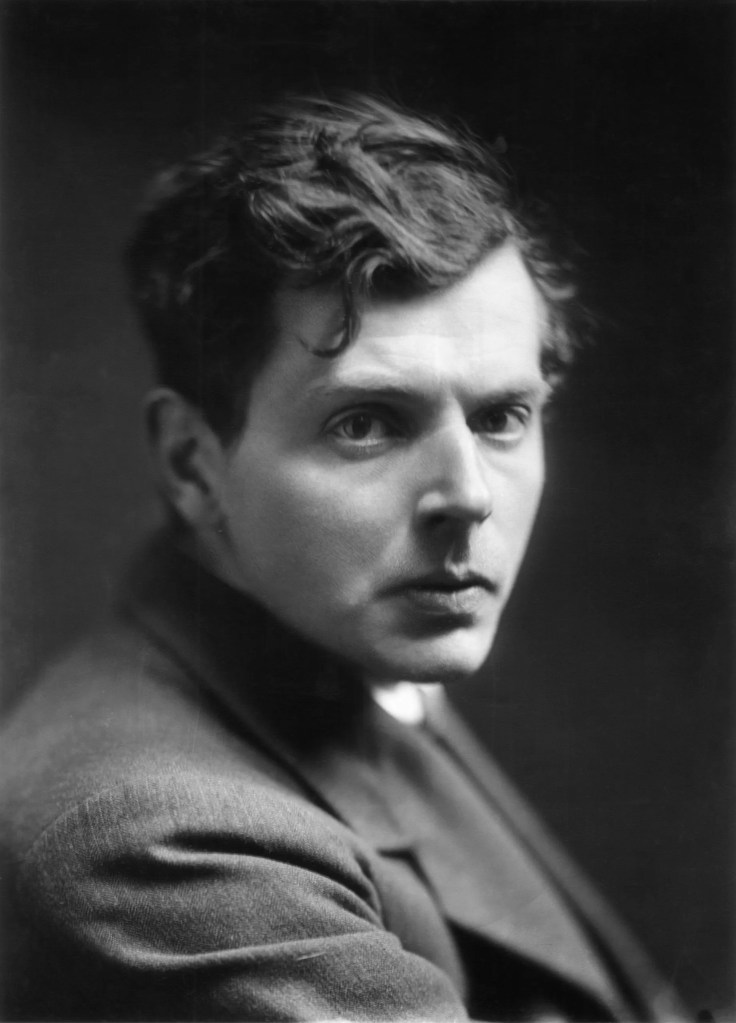

As Bridge was finishing the score of these pieces in May 1916, the 25-year-old poet and composer Ivor Gurney was marching with the 2nd/5th Gloucester Regiment towards the fields of Flanders. Later in that year, Gurney was one of the “lucky” survivors of the Battle of the Somme, but a year later he inhaled poison gas near Passchendaele and was sent to a series of hospitals back in Britain. Eventually – in October 1918 – he was discharged from the army with “deferred shell-shock”.

There’s little doubt that Gurney’s wartime experiences exacerbated a pre-existing mental health problem, which led to suicide threats and erratic behaviour. In September 1922, following four prolific years of composition and poetry, he was committed to an asylum in Gloucester, and in December he was moved to the City of London Mental Hospital (based in Dartford, Kent) where he spent the rest of his life (he died in 1937).

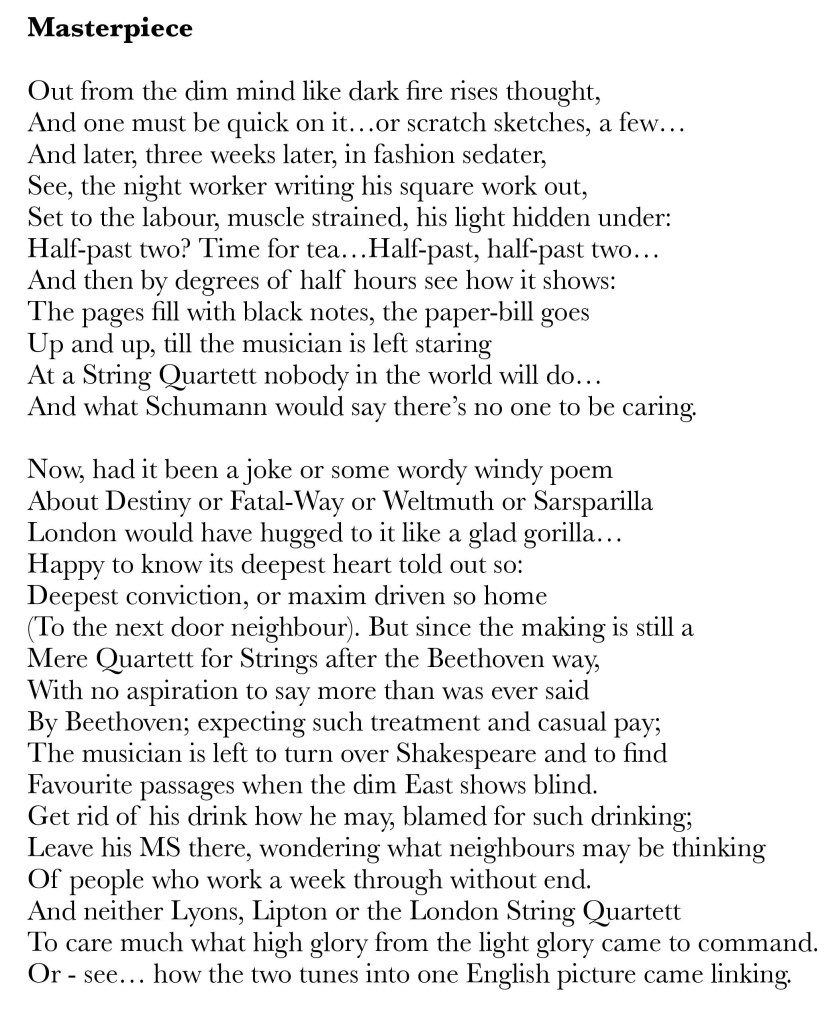

Gurney continued to write music and poetry and, though justly famous for his war poetry and evocations of his beloved Gloucestershire (the title of his first published collection, Severn and Somme, sums this up), he also gives us occasional glimpses into his everyday life. One such poem is Masterpiece – a fascinating insight into the composition of a string quartet in a fairly lighthearted tone (the title is surely tongue-in-cheek) – in which he links poetry and music: two equally important art forms for Gurney. The poem has been dated to November-December 1924: Gurney marked the manuscript “27th month” (i.e. of incarceration).

Ivor Gurney isn’t unusual for a poet in sometimes using a sort of private language – turns of phrase where only the poet really knows what is meant, or references to things or places that have particular significance to the writer, but that we as readers have to guess at and interpret, a bit like being a detective at a crime scene. This is to say that what follows is a personal interpretation and is not to be taken as a definitive reading.

The black humour of the poem lies in the frustration felt by the creative artist who can’t stop creating, but knows that his work will not be read or performed: a String Quartett nobody in the world will do.

We witness the process of composition – from the flashes of inspiration to the weeks-long working out of sketches, trying not to be distracted by the non-understanding neighbours and people around him, including, possibly, the nursing staff calling when it’s time for tea: Half-past two? Time for tea… Half-past, half-past two…

The choice of Schumann as the composer/critic whose opinion no-one is interested in is surely not arbitrary: Robert Schumann is well-known for also spending his last years in a mental asylum. There is a self-awareness in this poem that is quite extraordinary for someone deemed not fit to manage in the outside world.

In the second part of the poem, Gurney pokes fun at the London literary (and by implication, musical) establishment. Here he conflates poetry and music, complaining that, even if the work did receive a performance, it would not get critical approval – either too serious, or not serious enough. (Weltmuth – a made-up word sounding pretentiously German – “world courage”; Sarsparilla – “sarsaparilla” – a herbal substance or drink, possibly administered in the hospital.) Sarsparilla/gorilla provides a cheap rhyme, but also introduces a childish surreal element that seems intended to provoke.

There is a very modern use of stream-of-consciousness word association going on here – an almost random choice of words and rhymes, that highlights the workings of the unconscious mind in quite a knowing way, I would suggest.

When the composer gets the audience’s indifference he was expecting, he is left to read his book of Shakespeare in the early hours (when the dim East shows blind) and turns to drink (tea, or something stronger?).

Word association continues with the “found poetry” of brands of tea: Lyons and Lipton, though the mention of the London String Quartet could also connect with Lyons’ Corner Houses – restaurants where live music was part of the experience (the quartet also gave “Pops” concerts in wartime London – quite possibly including the Bridge miniatures in their repertoire).

But there is one final possibility that I will put forward. It is known that Gurney had access to a gramophone in the asylum and even that record companies donated records to the institution. Could the final line refer to this very recording of the London String Quartet? Or – see… how the two tunes into one English picture came linking. And could the choice of the word “linking” (to rhyme with “drinking” and “thinking”) be a playful acknowledgement of Gurney’s fellow composer, Frank “Bridge”? Who knows?

Footnote: Gurney scholar, Dr Philip Lancaster, has informed me that at 7.30pm on 17th December 1924 the London String Quartet made a radio broadcast on the newly formed BBC, so this could also have been a prompt for the poem, or at least for particular references.

[Frank Bridge: Two Old English Songs – Sally in our Alley/Cherry Ripe. London String Quartet. Recorded New York, 13 March 1922]

Leave a comment