By 1922 the 10-inch 78 rpm disc was pretty much established as the norm for commercial recording. The 3 minutes or so that could fit on one side set the template for pop songs that continues to this day. Classical recordings were often released on 12-inch discs, which allowed for an extra minute or two, but it meant that most of the early recorded repertoire of classical music was restricted to short pieces or movements – often abridged – from longer works (though there are exceptions: the first complete opera recording – Verdi’s Ernani – was released in 1903 on 40 single-sided discs, which must have provided healthy exercise for its armchair listeners).

This recording of Beethoven’s first string quartet was one of the earliest complete recordings of a whole quartet – movements recorded separately on different dates, but with no cuts, and released on 7 sides. The Catterall Quartet was one of England’s finest chamber ensembles, led by the leader of the Hallé Orchestra (and later the first leader of the newly-formed BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1929), Arthur Catterall. This is quartet-playing at its best: equality of the four voices, flexibility in pulse, and effortless virtuosity when required.

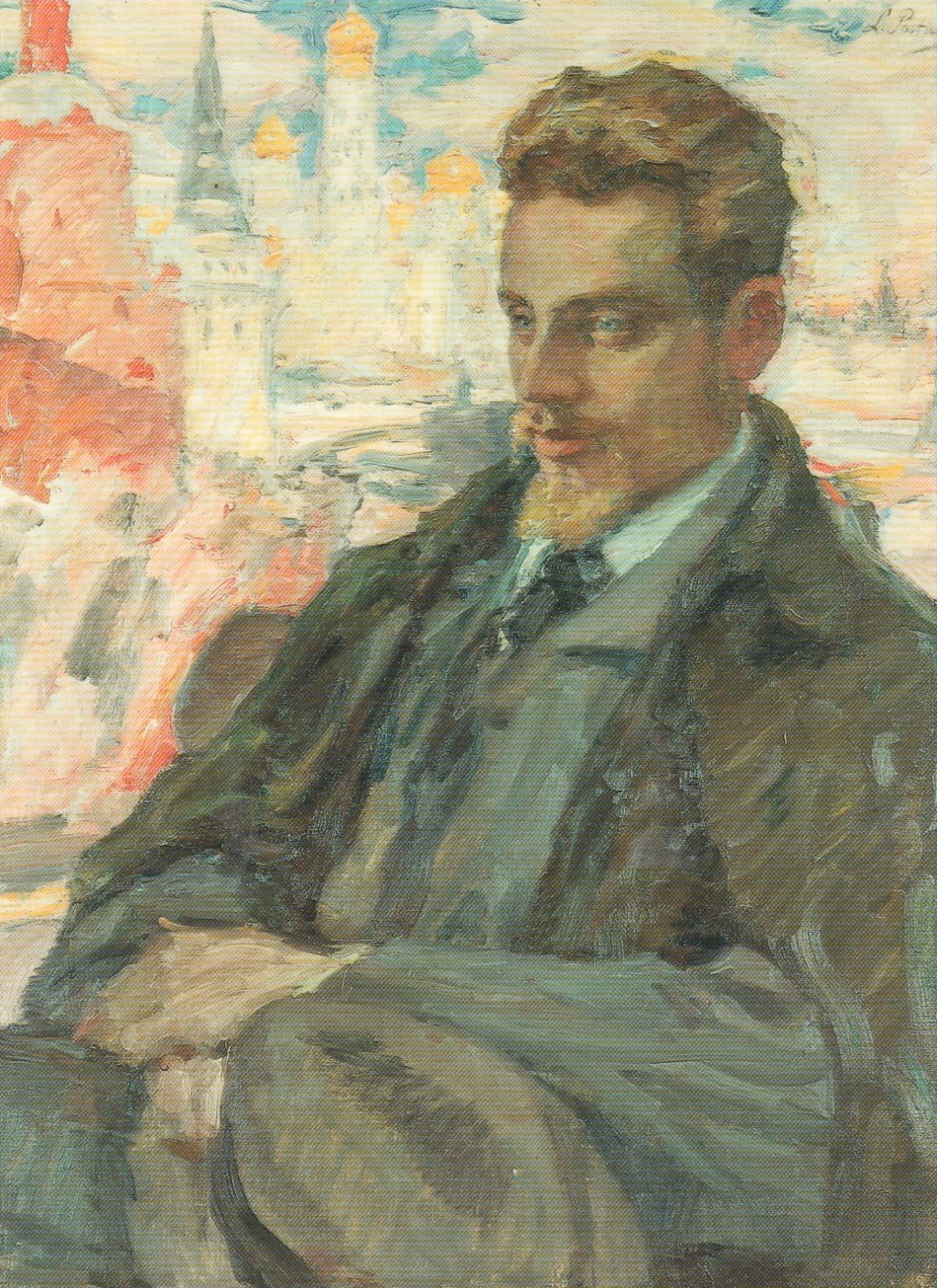

Meanwhile, in a chateau in Switzerland the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (born in Prague, 1875) was on a creative high. 1922 was the year in which he finished his monumental Duino Elegies (begun in 1912) and – almost as an afterthought – wrote in the space of a few weeks the 55 poems that comprise the Sonnets to Orpheus.

The sonnet cycle is an outpouring of songs in praise of creativity. And there is much about music and the importance of deep listening to the world as a way of finding our true selves. Although Rilke’s reputation has waxed and waned over the years (his extreme sensitivity and his detachment from ordinary life during his sojourns in the castles of the Alpine nobility can seem a bit precious), I would argue that just like we needed the hippies of the 60s or the punks of the 70s to shine a light on the hypocrisies of the modern world, so we still need the poetry of Rilke to remind us what is really valuable beyond our normal everyday concerns, or rather, to see what is valuable when we pay close attention to everyday things.

It can safely be said that Rilke would not have been a big fan of some of the more commercially successful recordings featured in this blog, especially as many of them were made in the USA. In a letter of 1922 he lets rip on the shallowness of much American culture:

Now there come crowding over from America empty, indifferent things, pseudo-things, dummy-life… A house, in the American sense, an apple or vine, has nothing in common with the house, the fruit, the grape into which the hope and pensiveness of our forefathers would enter… The animated, experienced things that share our lives are coming to an end and cannot be replaced. We are perhaps the last to have known such things.

from Briefe aus Muzot, trans. J.B. Leishman

While this outburst can easily be dismissed as the snobbish old-world ramblings of someone fighting an already lost battle against new-world modernity, it must be said that a culture that produced the empty fakery of a Trump presidency a century later might just be enough evidence to show that Rilke was not entirely wrong.

And if we remove the controversial cultural nationalism from the argument, maybe it’s worth attending to what Rilke is saying: that our relationship to the world around us needs to be deep-rooted and we need to listen, and respond.

In an extraordinary essay on Primal Sound, written in 1919, Rilke reveals his fascination with early recording technology: how a stylus on a wax disc can both record sound and reproduce that same sound. He then makes a quite complicated analogy, which I think can be summarised by saying that a creative individual’s relationship to the world is symbiotic or reciprocal – both receiver and transmitter.

And Beethoven was perhaps the ultimate receiver/transmitter: inhaling the spirit of the age and then practically launching the nineteenth century with this quartet (written 1798-1800, published 1801), with its adagio second movement providing the source of all future adagios up to Bruckner and Mahler and beyond.

What is it about this performance, and others like it, that makes us want to listen through all the limitations of early sound recording with all that excess surface noise? Yes, it’s partly our fascination with the traditions from which the musicians come. And there’s also that thrill of “being in the room” with the music being produced a 100 years ago – a sort of time travel. But isn’t it also that these musicians did not grow up like us surrounded by recorded music, whether we want to hear it or not? ”Live music” for them was just music. They were “perhaps the last to have known such things”.

One of Rilke’s sonnets seems especially relevant here. It can also be read as a prescient comment on the age of the smartphone, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, but in this context, Beethoven can be heard in the echo.

[Beethoven: String Quartet in F major, op. 18, No. 1. The Catterall Quartet. Recorded Hayes, Middlesex, 1922 & 1923]

Leave a comment