Here we are at post no. 12 in this series on recordings of 1922 and there’s been little mention of the m-word. 1922 is often seen as a crucial year in the history of Modernism – the year that saw the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. And both writers were encouraged by the poet Ezra Pound – a fetishist of “isms” (most notoriously, fascIsm), who designated 1922 as Year Zero.

Although 1922 might have been a key year for literary innovation, it doesn’t fit so well for music. Several groundbreaking works of musical modernism appeared somewhat earlier: Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in 1912 and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913, for example. And in the context of this blog series, which deals with the commercial realities of the early years of producing and selling records, very few of these works made it into a recording studio until several years later.

So how about we listen to this 3-minute “novelty rag” as a representative example of popular-culture modernism?

Instead of the bloated late-Romantic forces involved in Edgar Varèse’s Amériques – 142 players required for the original 1921 version – as an evocation of the modern urban world, why not a single piano player distilling the individual’s disoriented exhilaration at being swept up by the city that never sleeps?

Recent posts (here and here) have discussed the musical flexiblity of human movement – dances from an earlier age. But now, the new dances of the 20s have a frenetic regularity, and even if novelty rags were already a bit passé by 1922, if you were an American equivalent of a Bright Young Thing and you had your finger on the pulse, it was likely to be the pulse of an internal combustion engine.

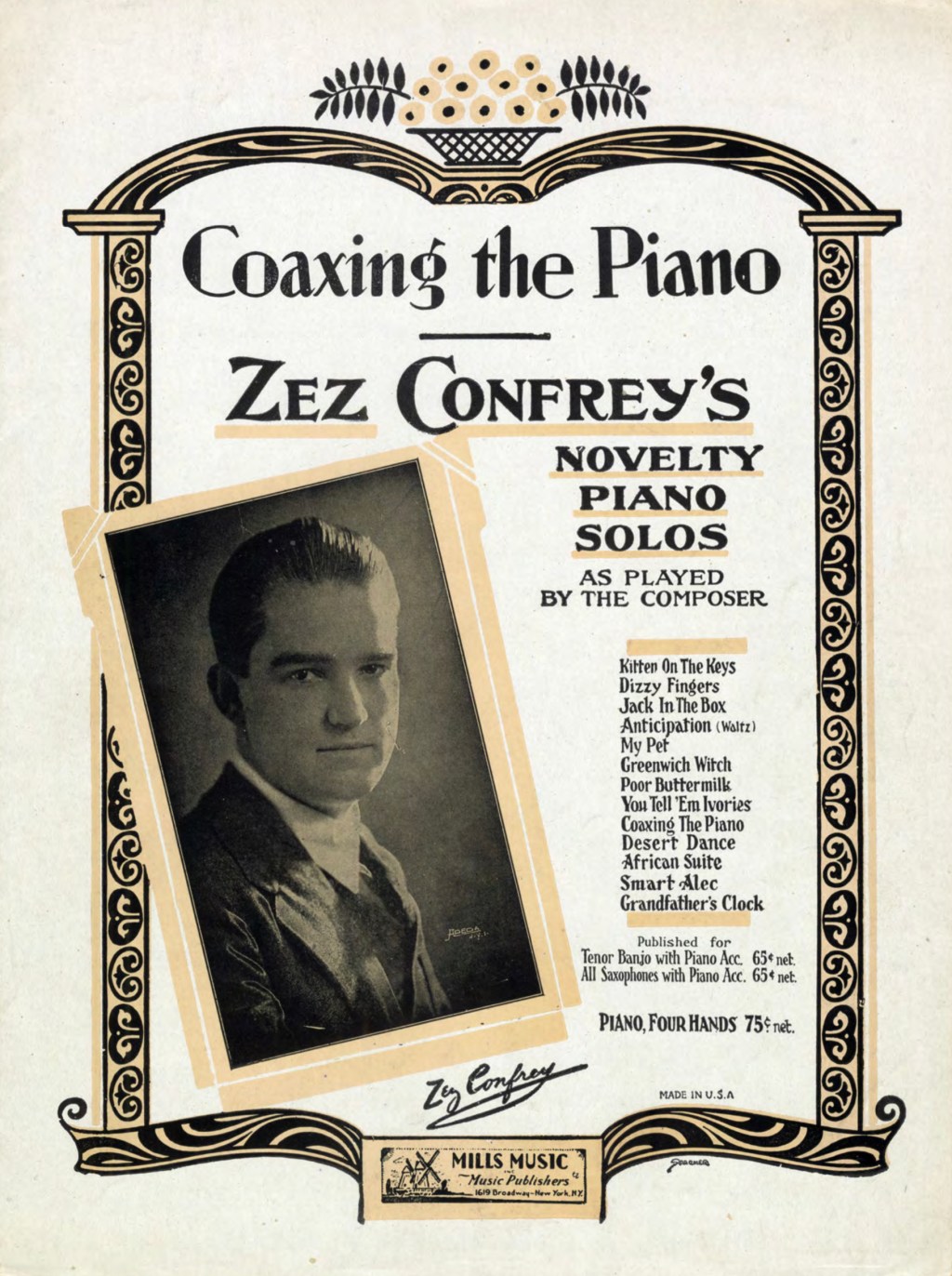

The composer and pianist Zez Confrey recorded many piano rolls. This piece – and others like it – is almost the player-piano process in reverse: sounding like it’s written for an automatic electrically-driven machine, but also able to be attempted by human fingers on an old-fashioned piano. The sheet music that was sold for amateur pianists – with its performance note above the title: “This number is very effective when played quickly and staccatto [sic]” – must have been a challenge that only the most proficient were ever likely to meet. (The version for piano, four hands was possibly slightly more achievable.)

If we need confirmation of Zez Confrey’s position at the cutting edge of popular music, we just need to have a look at the advertising for the concert that featured the famous premiere of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in 1924, where Confrey gets top billing:

And if Gerswhin’s experiment pushes jazz towards symphonic form, Confrey has gone in the opposite direction in this recording: a three-minute metropolitan microcosm of early 1920s New York, engraved in shellac on a 78rpm disc.

[Coaxing the Piano: Zez Confrey (composer and piano). Recorded New York, approx. November 1921, released 1922]

Leave a comment