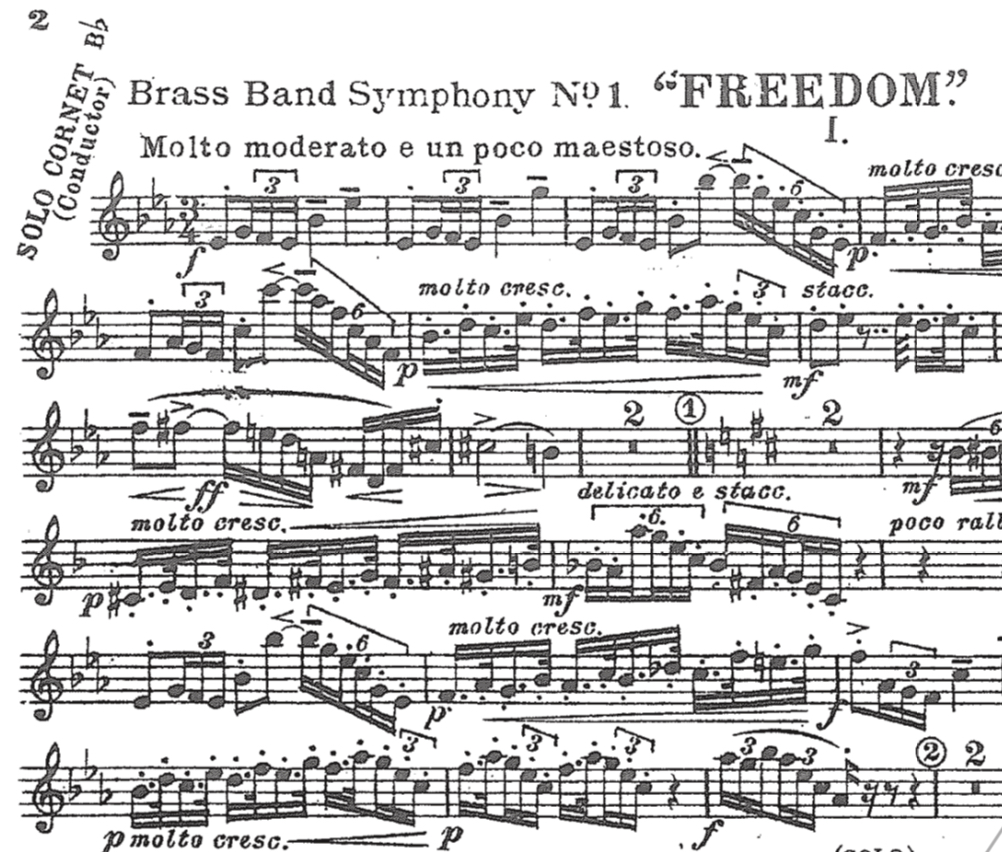

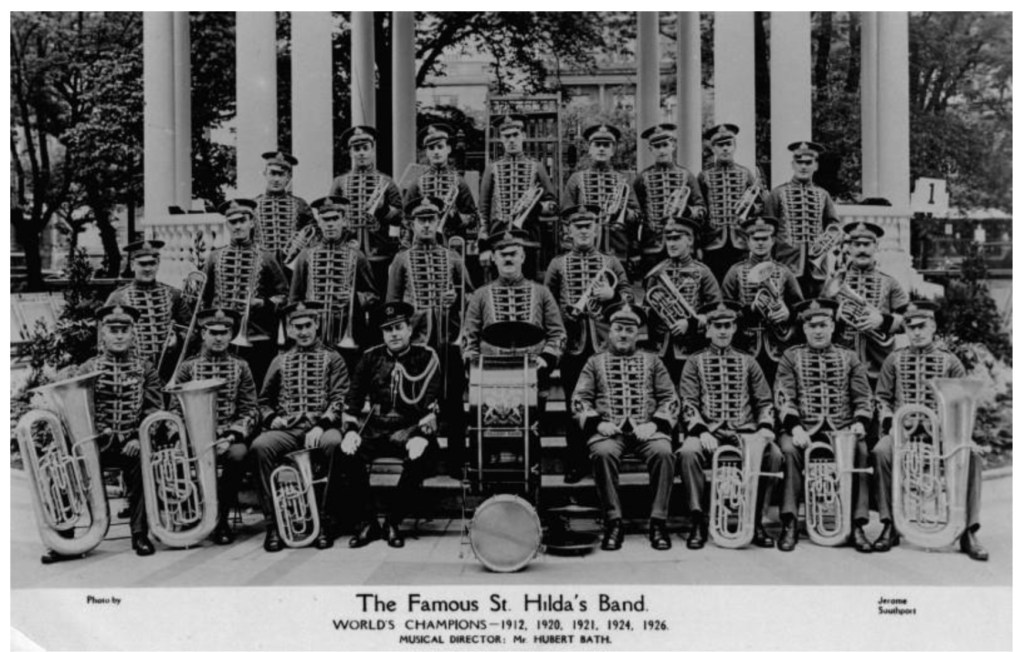

“Tone, tune, time reading, technique and expression of the finest culture.” These were the adjudicators’ comments when St Hilda’s Colliery Band won the Crystal Palace 1,000 Guinea Trophy and the Championship of the British Empire (later called simply National Championship) for the third time in 1921. The band had won in 1912, came second in 1913, and won again in 1920 (the competition was not held 1914-1919 because of the First World War). So it was a shock when the band came fourth in 1922. It seems likely that the recording session was booked on the assumption of another victory as it took place on September 25th – two days after the competition at Crystal Palace. (The score of Freedom recorded here is necessarily abridged to fit on the two sides of a 10-inch disc.)

Nevertheless, it’s an impressive performance for a fourth placed band. Just listen to the virtuosity of these players – mastering music as difficult as anything in the symphonic repertoire. The opening bars bear a passing resemblance to the Finale of Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony, with the difference that the equivalent of the busy string parts are played on brass instruments with three valves, or a single slide in the case of the trombones.

What makes this level of musicianship the more remarkable is the realisation that these players spent most of their waking lives working underground as coal miners in St Hilda’s Colliery, South Shields (on Tyneside, North-East England). Rehearsals were held in their limited spare time and leave was given for competitions as employers recognised the prestige that rubbed off from success (think football teams and sponsorship).

That colliery bands flourished at this time is partly due to the fact that coal miners were exempt from conscription during the war (with the exception of those Welsh miners who were sent to dig tunnels to lay explosives under German lines). Coal mining was one of the most dangerous forms of employment – 141 men lost their lives working at St Hilda’s Colliery during it’s 130 years of existence [source: Durham Mining Museum]. But men had a greater chance of survival down the pit than in the hellish trenches of the Western Front.

Part of the success of the St Hilda’s Band in these years (they want on to win the National Championship again in 1924 and 1926) was down to the work of William Halliwell who conducted them in all of their winning performances. In fact Halliwell has a still unbeaten record of conducting 17 first prizes in 26 years of the National Championships between 1910 and 1936. In 1922 alone he conducted 7 bands and they were all ranked in the top 10.

One can only imagine the feelings of the regular bandmasters who put in weeks and weeks of work training the band only for the glory to go to the star conductor who stepped in for the final few rehearsals, but he clearly was an expert in polishing a brass band. He vividly describes one such final preparation:

The band was very good by that time technically, but the general performance lacked vitality and imagination. It was my job to develop these qualities and the progress during that day might be described as something like lighting a fire. First the smoulder, then the glow, then the blaze.

From a speech to the Rotary Club of Wigan, 1925

Hubert Bath’s Freedom (Brass Band Symphony No.1) was representative of a new style of competition test piece. Before the war, the set work usually consisted of an arrangement of a well-known orchestral piece, such as the William Tell Overture. But as standards of playing got higher and higher, contemporary composers were commissioned to write new, ever more challenging pieces, a tradition that continues to this day. (For a more recent example of mind-blowing virtuosity, have a listen to Philip Wilby’s Masquerade.)

The extra-musical subject matter of these pieces often combined a non-conformist religious sensibility with a sort of patriotic escapism. It’s almost as if the revelatory visions of William Blake have been reborn a century later in the new brass band repertoire. The composer’s notes in this score describe an idyll that must have been out of the reach of most Tyneside miners:

First Movement: In God’s fresh air, under the open sky, we stretch our arms to the great spaces, breathing the winds and contemplating the gentle sweetness of Nature itself. This is Freedom.

Second Movement: And then, the quiet interlude of Romance, the trees, the meadows, the scent of the flowers, the little drifting clouds, and — Love. This, too, is Freedom.

Third Movement: And then, again, that other insuperable gift of Laughter, fresh and light as the salt sea breezes over the hilltops which have fluttered their songs across the laughing waves. This is Joy, Love, Vigour, and— This, also, is Freedom.

Within a decade, the pastoral idyll had completed its move to the countryside, well away from the grime of heavy industry – most prominently in the “trilogy” of Holst’s A Moorland Suite (1928), Elgar’s The Severn Suite (1930), and Ireland’s A Downland Suite (1932), works that are just as poignant today with our awareness of manmade environmental degradation, not least that caused by the burning of coal and other fossil fuels.

But the modern style of test piece was not universally popular. In a review of the 1922 Championship, composer and conductor James Ord Hume wrote:

From a personal point of view, and from many years’ experience, both as a judge and writer of brass band music, I cannot agree that brass bandsmen are in favour of the test piece of the last decade. The fact remains that they have never become popular as test pieces, and they never will become popular, either with contest committees or with bands or audiences… Brass bands are a popular institution, and they are undoubtedly the ”people’s orchestra”, and the people enjoy popular brass band music just the same as another class of the musical public enjoy their orchestra or oratorio. It is the brass band that brings the opera, musical play, oratorio, and other musical arrangements to the humble worker, who otherwise would never hear such music; and they prefer this to music that can only be played or heard by some twenty bands out of a total of over 30,000 bands in Great Britain alone.

Musical News and Herald, September 30, 1922

So let’s whet the appetite of the humble worker with popular pieces but save the challenging stuff for “another class of the musical public”. Try telling that to the countless players who have populated the brass sections of British orchestras over the past century, many of whom came through the brass band movement. And how many aspiring young musicians have had their musical horizons widened by local bands when official teaching provision has failed or simply not existed?

As for the St Hilda’s band, they managed to survive when the pit was closed down in 1925 by touring and earning income from performing concerts, but the downside of this was that they were deemed to be a professional band and so were disqualified from competing in the National Championships after their fifth and final victory in 1926. They managed to keep going for another decade until the realities of running a full-time brass band during an economic depression caught up with. them. Their eventual demise was marked with this unassuming advert in the Musical Progress and Mail of December 1937:

[Hubert Bath: Freedom (Brass Band Symphony No. 1), St Hilda Colliery Band. Recorded September 25, 1922]

Leave a comment