A masterly transcription of an orchestral piece by Bizet. With minimal changes to the original (written 50 years before these recordings, in 1872) – just a few chromaticisms in the figurations and an occasional spicy chord – it has been transformed into a Rachmaninoff-sounding piano miniature. It’s as though Rachmaninoff recognised his doppelgänger in the earlier composer:

If you are a composer you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my pianoforte interpretations, color. So you can make music live. Without color it is dead.

From an interview with Rachmaninoff, Musical Opinion, 1936

I’ll come back to the concept of musical colour later.

Two recordings of the same piece made 40 days apart in early 1922, using the most advanced technologies of the time.

The first, an acoustic recording of Rachmaninoff playing a Steinway model D in the Victor recording studio in Camden, New Jersey: two large recording horns (one for the treble, one for the bass strings), whose diaphragms sent vibrations to a stylus engraving a groove into a soft wax master disc.

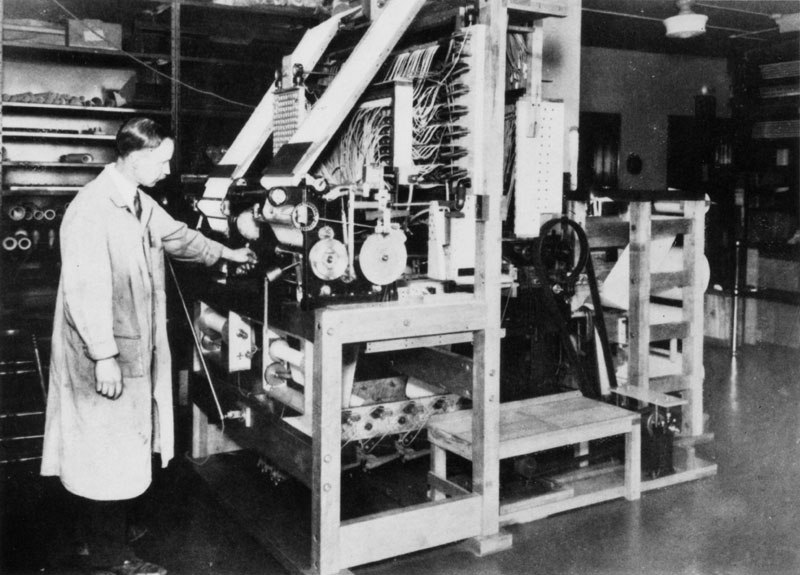

The second, a modern recording of a restored Ampico reproducing player-piano, playing a piano roll containing an “imprint” of Rachmaninoff’s performance on a Mason & Hamlin piano in Ampico’s New York studio.

Both of these technologies were to be superseded in the following few years: acoustic recording by electric recording using microphones and amplifiers in 1925, giving a greater dynamic and frequency range; Ampico’s reproducing piano by its model B system in the same year, allowing more subtleties of the original recording to be imprinted and reproduced.

So which of the two recordings is closer to hearing Rachmaninoff playing the piano? On first impressions, the piano roll is the more impressive. We are hearing a modern recording – we can hear more detail of sound and even see the ghostly movements of the piano keys. And other piano rolls have even been subject to modern computer technology, going so far as to produce a virtual reproduction of Rachmaninoff’s hands.

The headline in the above link rings some very high-frequency alarm bells for me: “This AI has reconstructed actual Rachmaninov playing his own piano piece” it states confidently. That “actual” is doing a lot of work in the headline and brings me to the “actual vs virtual” dilemma.

What “actually” went on in the process of producing a piano roll? I’m not going to get into the specifics of the electronics and hydraulics involved. It’s enough for my purpose to know that at this time, rolls could record and reproduce only notes, rhythm, and articulation. In other words, they couldn’t deal with musical colour – the “most important thing” for Rachmaninoff as a performer. For the subtleties of dynamics involved in touch and tone, an army of technicians was employed to make thousands of adjustments to the roll in an attempt to replicate the playing of the original performer, overseen by the musician’s personal editor: in Rachmaninoff’s case, Edgar Fairchild – an accomplished pianist in his own right.

So not so different from a modern recording process’s editorial box of tricks for correcting or ’improving” an original take.

Now let’s take a slight detour to the aesthetics of listening to live (and “in-person”) versus recorded forms of music. The medium that often blurred this distinction was radio, which was just starting to get going in 1922 (the year the BBC was founded). Interestingly, Rachmaninoff refused to make radio broadcasts, which are yet another form of “at home” listening, involving mainly unedited broadcasts of live concerts. His views are worth quoting in full as his reasons are not to do with the technical quality of sound, but raise deeper issues.

Radio is not perfect enough to do justice to good music. That is why I have steadily refused to play for it. But my chief objection is on other grounds. It makes listening to music too comfortable. You often hear people say “Why should I pay for an uncomfortable seat at a concert when I can stay at home and smoke my pipe and put my feet up and be perfectly comfortable?” I believe one shouldn’t be too comfortable when listening to really great music. To appreciate good music, one must be mentally alert and emotionally receptive. You can’t be that when you are sitting at home with your feet on a chair. No, listening to music is more strenuous than that. Music is like poetry; it is a passion and a problem. You can’t enjoy and understand it merely by sitting still and letting it soak into your ears.

Interview with Rachmaninoff for Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Paris 1927

Of course, the argument could apply equally to records, listened to at home with your feet on a chair (the cynic in me suggests that maybe the fees for radio broadcasts were not as generous as his deals with RCA Victor), not to mention listening to music on your iPhone whilst scrolling through your Facebook feed, but the phrase that I love – and that might just become a personal motto – is that music is “a passion and a problem”. Rachmaninoff was not just the “heart on his sleeve” romantic of conservative repute, but a musician – both as composer and performer – of both heart and head (he was often regarded as quite a cerebral performer by his contemporaries). His objection to some forms of musical modernism was that they often prioritised head over heart. But what is clear from the words above is that Rachmaninoff wanted the listener to take an active part in the musical process – to be a problem solver as well as a fully rounded receptive human being.

So maybe the argument over which recording represents the “real” Rachmaninoff is less important than the more exciting realisation that we – as listeners – can become virtual editors or virtual “master perforators” of the music that we hear, whatever the technical medium that presents it.

[Bizet, arr. Rachmaninoff: Menuet from L’Arlesienne Suite No. 1. Recorded Camden, New Jersey, 24 February 1922]

[Bizet, arr. Rachmaninoff: Menuet from L’Arlesienne Suite No. 1. Recorded on Ampico piano roll 6 April 1922]

Leave a comment