A Jewish Russian-Hungarian band leader (Dajos Béla) and his Berlin-based salon orchestra (Künstler-Kapelle) playing an Arabian shimmy (“Arabischer Shimmy”) by an American composer (Ted Snyder) written in response to a book by an English author (Edith Maud Hull), and made popular by a hit silent film (The Sheik), starring an Italian actor (Rudolph Valentino). What is going on?

This is the story of a hit tune, a blockbuster film, and a bestselling novel. And all throw a spotlight on the sexual politics and colonial attitudes prevalent in American and European popular culture in 1922.

First, the tune.

A quick bit of musical analysis: the tune uses the so-called “Arabic scale” or “double harmonic major scale” (containing two major seconds: F, Gb [only in the harmony here], A, Bb, C, Db, E) – often used by composers to evoke an all-purpose oriental character, as in the Bacchanale from Saint-Saëns’s opera Samson and Delilah (1877). Throw in some cymbal crashes, a sprinkling of castanets (actually they sound like wood blocks here – they’re louder, I guess) and season with a dash of wailing oboe, and we’re almost there. All that’s needed is a cheeky quote from Grieg’s Peer Gynt (at 1’33’’), whose eponymous hero also ends up in the North African desert, and we’re done.

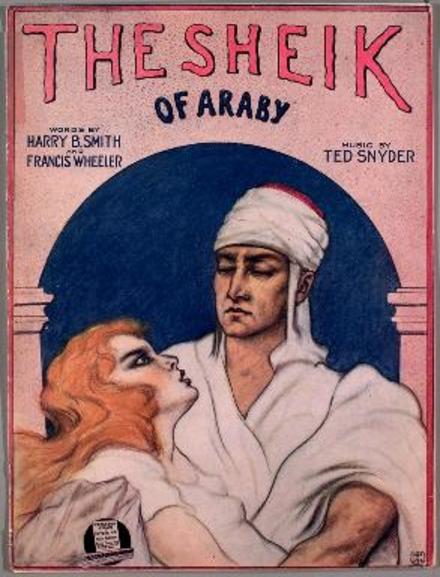

Ted Snyder’s Tin Pan Alley tune – titled fully as The Sheik of Araby – was soon taken up by musicians and recording companies far and wide. There are several other versions from 1922, including a very similar arrangement by Eleuterio Yribarren and his Red Hot Pan American Jazz Band recorded in Buenos Aries.

The tune quickly became what was then a new phenomenon – a jazz standard. There are countless recorded versions from the following decades that together make a mini history of jazz styles. As most versions concentrate on the second half of the tune, there is not much left of the oriental flavouring. Here is my personal selection:

- 1922 – A virtuosic ragtime version for piano roll by Zez Confrey

- 1932 – Duke Ellington – including a rare soprano sax solo (1’29″) from Johnny Hodges, the regular alto player (apparently he visited Sidney Bechet’s apartment the night before the recording for a lesson).

- 1937 – Stephane Grapelli and Django Reinhardt doing their Hot Club du France thing.

- 1937 – possibly my favourite version: Art Tatum at his most inventive, using the whole range of the piano in this miniature masterpiece – the musical equivalent of drinking the perfect espresso. His rare inclusion of the first part of the tune allows for about 15 seconds of almost Debussyian harmony (from 0’28″), which also highlights the tune’s similarity to Gershwin’s It Ain’t Necessarily So of two years earlier.

- 1939 – Jack Teagarden sings and plays on the B side to another orientalist tune, Persian Rug.

- 1941 – An early experiment in multi-tracking: Sidney Bechet playing clarinet, soprano sax, tenor sax, piano, bass, and drums.

- 1942 – a Nazi propaganda version by Charlie and His Orchestra. Although jazz was officially banned by the Nazis, this German swing band was formed to broadcast on international shortwave radio. As with their other productions, it starts with the original lyrics, then is hijacked by anti-British propaganda..

- 1945 – The 19-year old Oscar Peterson in his first recording session: boogie-woogie with a hint of early rock and roll.

- 1962 – And that mention of rock and roll leads nicely to the most unlikely version of all. Forty years after the song’s first recording, The Beatles (with George Harrison on vocals and Pete Best on drums) recorded The Sheik of Araby as part of their unsuccessful demo session for Decca, whose executives judged that “the Beatles have no future in show business”.

What about the book that spawned the song and then the film? Marketed in a recent rewrite (or rip-off?) as ”Pride and Prejudice in the Desert”, E.M Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik (which sold in the millions soon after publication) follows the Jane Austen plot-line of an independently-minded woman and an overbearing man, who come to love each other in the end. But the narrative – set in French colonial Algeria – is overlaid with the culture clash of European woman meets Arabian man, made horrifyingly morally dubious – to say the least – by the man raping the women after she is captured (between chapters in the book, between scenes in the film) and finally falling in love with her. The dénouement comes when he reveals that he is not an Arab after all. His father was English, his mother Spanish, so all is well!

The two live happily ever after in the desert, leaving the reader with the final specter of an aristocratic English couple “gone native,” it is true, but reigning imperialistically over the unruly Bedouin tribes of the Sahara in an area which was nominally under French colonial control.

Hsu-Ming Teo, 2010

For any interested readers, there are many online articles of literary criticism about the novel, but a good summary of the issues of sexual, racial, and colonial politics (and how the differing post-First World War experiences of the UK and USA are reflected in the English novel and the American film) can be found in the article quoted above.

The film and its sequels made Valentino a star. And the fashion in Europe for all things oriental (however vague and stereotyped that fashion) increased exponentially from this time on, and was given a huge boost by the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt in November 1922.

The cartoon version of sheiks and Arabia has never really disappeared – there’s even a Muppet rendition of the song – and newly written “desert romance” novels increased in popularity in the early 2000s.

What’s missing, of course, is any voice from the Arab world itself. In 1922 much of that world was ruled under the Mandate system, established after the First World War by the League of Nations (principally Britain and France) because – according to Article 22 – the local peoples were not considered “able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world”. The areas’ governance was to be “entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake this responsibility”.

And a final footnote to show just how far the meme of the desirable sheik has spread. In Faroese – the language of the Faroe Islands where I live – the common slang word for boyfriend is “sjeikur” (i.e. sheik).

[The Sheik – Arabischer Shimmy (Ted Snyder), Künstler-Kapelle, Dajos Béla. Released 1922]

Leave a comment